A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution

“Square knapsacks are most convenient …”

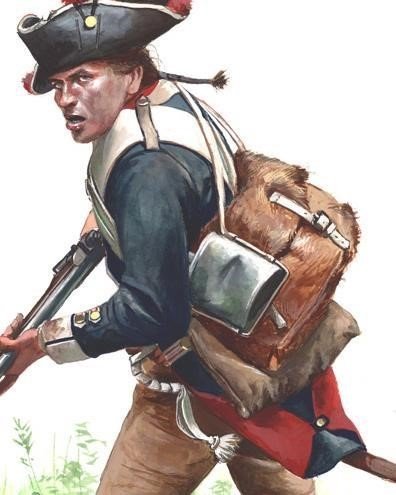

This post began with the vague idea of discussing the 17th Regiment’s recreated knapsack. To my mind it is the only one that comes close to representing the design of the originals likely carried by mid-war (and possibly late-war) British soldiers. But that set me to ruminating on how the double-pouch knapsack (such as the Benjamin Warner pack at Fort Ticonderoga and the one pictured below in the 71st Regiment’s 1778 order book) came to be. The following narrative, based on both primary and, admittedly, circumstantial evidence, attempts to trace that transformation, and (spoiler alert) leads the author to think it very likely the double-pouch pack was a wartime innovation.

Drawing of knapsack from British 71st Regiment 1778 order book. This is likely evidence that double-bag knapsacks, undoubtedly of linen, were being used by British troops at least by 1778. Note that food was to be carried in one bag, and a minimum of necessaries (“1 pair of shoes,” “1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt, “1 Pr. stockings”) in the other. Continental Army twoshoulder-strap double-bag packs were probably copied from British knapsacks. The Warner knapsack (probably issued in 1779) had two storage pouches; orders for American army knapsacks in 1782 stipulated, “Let them be made double, & one side painted.” Standing Orders of the 71st Regiment, 1778, Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell, National Register of Archives for Scotland (NRAS 28 papers), Isle of Canna, Scotland, U.K.(Knapsack drawing courtesy of Alexander John Good.)51

[gallery ids="3610,3619" columns="2" link="file" size="full"]Recreated Knapsacks, 17th Regiment

There are occasions (actually, many occasions) when my understanding runs on a very slow burn. In this vein, researching and writing about knapsacks used before, during and after the American War (1775-1783), eventually led me to the conclusion that British knapsack design took a right turn early in that conflict. Is my conclusion conclusive? No, it isn’t, as there are missing pieces in the records, but the possibility (or probability) is intriguing.

* * * * * *In his 1768 treatise System for the Compleat Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry Bennett Cuthbertson wrote,

Square knapsacks are most convenient, for packing up the Soldier’s necessaries, and should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen: a certain size must be determined on for the whole, and it will have a pleasing effect upon a March, if care has been taken, to get them of all white goat-skins, with leather-slings well whitened, to hang over each shoulder; which method makes the carriage of the Knapsack much easier, than across the breast, and by no means so heating.9

Cuthbertson reveals here several notable clues. First, of course, is his statement touting the superiority of “square” knapsacks with two shoulder slings. The 1751 Morier figures and the circa 1765 painting “An Officer Giving Alms to a Sick Soldier” by Edward Penny (1714-1791) show soldiers wearing single-shoulder-strap skin packs, so Cuthbertson’s square knapsack was a relatively recent innovation. Mr. C. also states square packs “should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen” and “a certain size must be determined on for the whole …” ”[M]ade with a division.” That, to me, indicates Cuthbertson is speaking of a single pouch knapsack, like the David Uhl and Elisha Grose packs, while his remark about determining size can only mean no standard design had yet been settled on. And his reference to “all white goat-skins” refers to a knapsack likely made entirely of leather, again like the Grose knapsack. Both pre-war and in the war’s early years leather seems to have been the preferred material for many, perhaps most, knapsacks.

(For references to leather packs see sections titled “Leather and Hair Packs, and Ezra Tilden’s Narrative” and “The Rufus Lincoln and Elisha

Gross Hair Knapsacks” in “’Cost of a Knapsack complete …’: `This Napsack I carryd through the war of the Revolution,” Knapsacks Used by the Soldiers during the War for American Independence’” http://www.scribd.com/doc/210794759/%E2%80%9C-This-Napsack-I-carryd-through-the-war-of-theRevolution-Knapsacks-Used-by-the-Soldiers-during-the-War-for-American-Independence-Part-1-of-

%E2%80%9C-Cos ; see also, Al Saguto, “The Seventeenth Century Snapsack” (January 1989) http://www.scribd.com/doc/212328948/Al-Saguto-The-Seventeenth-Century-Snapsack-January-1989 )

[gallery ids="3628,3638" columns="2" size="full"]Detail from David Morier, “Grenadiers, 46th, 47th and 48th Regiments of Foot, 1751” http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection-search/david%2520morier

Based on the writing of Massachusetts militia colonel Timothy Pickering (below), sometime prior to 1774, packs like the one Cuthbertson described seem to have been adopted by at least some British regiments:

A knapsack may be contrived that a man may load and fire, in case of necessity, without throwing down his pack. Let the knapsack lay lengthways upon the back: from each side at the top let a strap come over the shoulders, go under the arms, and be fastened about half way down the knapsack. Secure these shoulder straps in their places by two other straps which are to go across and buckle before the middle of the breast. The mouth of the knapsack is at the top, and is covered by a flap made like the flap of saddlebags.- The outside of the knapsack should be fuller than the other which lies next to your back; and of course must be sewed in gathers at the bottom. Many of the knapsacks used in the army are, I believe, in this fashion, though made of some kind of skins.20

Pickering, too, refers to packs made of leather, infers that they had only a single pouch, and adds that the closing flap resembles those on saddle bags of the time. Period examples have closing flaps similar to those on the Uhl (linen) and Grose (bearskin) knapsacks.

So, just when were double-pouch knapsacks (like Benjamin Warner’s 1780 pack) first introduced to British troops in America? A drawing from a 1778 71st Regiment order book found and shared by Alexander John Good may provide the answer. That image shows a very simple double-pouch knapsack, with food placed in one pouch and “1 pair of shoes,” 1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt,” and “1 pr stockings” in the other. (It is interesting that this apportionment mirrors that of the “new Invented Napsack and haversack” used by some Whig units in 1776, 1778, and possibly 1777, but more on that later).

See the timeline of British Knapsacks at the bottom of this article.

British regiments already in America at the beginning of the war had knapsacks, but we have no idea of their design. At this time, given what we know of pre-war packs from period images and the comments of Cuthbertson and Pickering, I can only surmise that early-war (1775-1777) British knapsacks were leather (goatskin?), possibly linen, “square” models, with a single pouch (possibly with a divider to separate a spare pair of shoes from the other necessaries), and two shoulder straps. They also could not easily accommodate a blanket, an item deemed necessary for service in North America. British, French, and German troops campaigning in Europe did not carry blankets on the march, those coverings being carried in the same wagons as the regimental tentage. The packs (tournisters) German troops carried while serving in the American War still could not carry a blanket, and we are still unsure how, or even if, German troops carried blankets on the march.

Supply documents for the British Brigade of Guards, 1776 to 1778, including numbers of knapsacks issued and the use of blanket slings on campaign, and generate some interesting questions.

[Numbers of knapsacks needed and requested]

List of Waggons, Tents, Camp necessaries &ca for the Detachment from the Three Regiments of Foot Guards, consisting with their Officers of 1097 men destined to Serve in North America.

February 5th 1776 …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks(Loudoun p.213) (see also WO4/96 p.45 7 Feb. 1776 Barrington to Loudoun)[Knapsack pattern]Memo Brig. Gen. Edward Mathew to John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun 16 Feb. 1776 "Memorandum concerning the [Guards] Detachment Fryday Feb 16 1776" "Light Infantry Company. Colo. Mathews applies for the proper Clothing.proposes: To cut the 2nd Clothing of this Year into Jackets. --Caps, Colo. M to produce a pattern --Arms, The Ordnance will deliver them with the others. a fresh Application.Accoutrements, upon the plan of the light Infantry. Colo. M--Bill Hook and Bayonet in the same case. Colo M.-- ""Gaiters and Leggins Knapsack -- Genl. Tayler has a pattern. Nightcaps -- Colo. M to shew one Canteens -- to see a Wooden one."(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6510)[Altering knapsacks] Memo Mathew to Loudoun 28 Feb. 1776

"Estimate of the Extra expence of the Necessary Equipment of the Detachment from the Brigd. of Foot Guards Intended for Foreign Service"

Alteration of the Mens Knapsacks .6 [pence]To Receive from the Goverment in Lieu of Knapsacks 2.6Allowance from Govermt. to each Man for a Knapsack 2.6(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6514)[Fitting knapsacks] Regimental Order, London 7 March 1776The 1st Regt. will draught the 15 men "by Lot out of such Men as are in every respect fit for Service."2nd and 3rd Battalion to draught Sat the 9th 1st Battalion on Sun the 10thA return to be sent in of the name, age and service of the men. Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

"The Extraordinary necessaries furnish'd are not to be deliver'd to the Men till they are in their first Cantonments."

(First Guards)[List of soldiers’ necessaries, including knapsacks] Brigade Orders, London 13 March 1776"The Necessarys of the Detachment are to be Compleated to the following Articles -- Three ShirtsThree Pair worsted StockingsTwo pair of Socks 7/ 1/4 pr. PairTwo pair of ShoesThree pair of Heels and Soles 1/2 d pr. pairTwo Black StocksTwo Pair of Half Gaiters 1s/ pr. pairOne Cheque Shirt 3/9 dA Knapsack (2/6 d Allowed by Government)Picker, Worm & TurnscrewA Night Cap"(Scots)

A little over a month later, on 26 April 1776, the three Guards Battalions set sail for North America.

With all the trouble taken to procure knapsacks for the Guards Brigade, those packs seem to have either been left aboard the transports when the Guards went ashore at Long Island, New York or sent back on board after landing. Several 1776 documents mention knapsacks or the lack thereof during the New York campaign.

"[Guards] Brigade Orders August 19th [1776.]When the Brigade disembarks two Gils of Rum to be delivered for each mans Canteen which must be filled with Water, Each Man to disembark with a Blanket & Haversack in which he is to carry one Shirt one pair of Socks and Three Days Provisions a careful Man to be left on board each Ship to take care of the Knapsacks. The Articles of War to be read to the Men by an Officer of each Ship."(Thomas Glyn, "The Journal of Ensign Thomas Glyn, 1st Regiment of Foot Guards on theAmerican Service with the Brigade of Guards 1776-1777," 7. Transcription courtesy of Linnea M. Bass.)General (Army) Orders 20 August 1776"When the Troops land they are to carry nothing with them but their Arms, Ammunition, Blankets, & three Days provisions. The Commandg. Officers of Compys. will take particular care that the Canteens are properly fill'd with Rum & Water & it is most earnestly reecommended to the Men to be as saving as possible of their Grog." (1) (2)Brigade Orders 23 August 1776 [the day after their landing on Long Island]"the Brigade will Assemble with their Arms Accoutrements Blankets & Knapsacks to Morrow Morning at 5 oClock upon the same ground. . ." (2) (1)Brigade Orders 24 August 1776"the Commanding offrs of Battns may send their Knapsacks on board of Ships again if they find any ill Conveniency of them." (2) (1)It seems that many Crown soldiers used only slung blankets during the 1776 campaign, perhaps due to the “ill Conveniency” of their knapsacks, whatever that may mean. Here are two more 1776 references to carrying only blankets and blankets on slings:Orders, 4th Battalion Grenadiers (42nd and 71st Regiments), off Staten Island, 2 August 1776: "When the Men disembark they are to take nothing with them, but 3Shirts 2 prs of hose & their Leggings which are to be put up neatly in their packs, leaving their knapsacks & all their other necessaries on board ship which are carefully to be laid up by the Commanding Officers of Companys in the safest manner they can contrive."Capt. William Leslie, 17th Regiment of Foot, 2 September 1776, “"Bedford Long Island Sept.2nd 1776…

The Day after their Retreat we had orders to march to the ground we are now encamped upon, near the Village of Bedford: It is now a fortnight we have lain upon the ground wrapt in our Blankets, and thank God who supports us when we stand most in need, I have never enjoyed better health in my Life. My whole stock consists of two shirts 2 pr of shoes, 2 Handkerchiefs half of which I use, the other half I carry in my Blanket, like a Pedlar's Pack."61

Preparing for the 1777 campaign the British Guards were slated for another knapsack issue:Secretary at War William Barrington, 2nd Viscount Barrington to Loudoun 7 Sept 1776 His Majesty Orders that for the 1777 Campaign the Detachment is to receive the following CampNecessaries …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks10 Powder Bags(WO4/98 p. 144)Note: Correspondence on pages 150, 157, 171 indicates that only 150 knapsacks per regiment in America were supplied for the 1777 campaign. [That would make 450 total for three battalions.] And in March 1777 the following order was issued:[Guards] Brigade Orders 11 March 1777"The Waistbelts to Carry the Bayonet & to be wore across the Shoulder. The Captains are desired to provide Webbing for Carrying the Mens Blankets according to a pattern to be Seen at the Cantonment of Lt. Colo. Sr. J. Wrottesleys Company. The Serjeants to Observe how they are Sewed."(1) From an original manuscript entitled "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" which is actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day theBrigade for American Service was formed. Manuscript Dept., William L. Clements Library, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor. (Microfilm available for loan.)

So, were British knapsacks in use up to and including the year 1777 both single-pouch and incapable of accommodating a blanket? Were blanket slings used to carry blankets with knapsacks as well as without? Or were the knapsacks used by Crown forces at the time merely considered cumbersome, and blanket slings thought to be more proper for campaigning soldiers. Added to those questions, we are not at all certain how British soldiers carried their blankets even after double-pouch knapsacks came into use.

To Be Continued...

British Knapsack Timeline, 1758-17941758-1765 (and earlier), Single-pouch purse-like leather knapsack carried by British troops, as pictured in paintings by David Morier (1705-1770) and Edward Penny, R.A. (1714-1791). These knapsacks could not accommodate a blanket.1768, Cuthbertson recommends “square” knapsacks with two shoulder straps.1771, Painting of a private soldier of the 25th Regiment of Foot shows him wearing a hair pack with two shoulder straps. His knapsack seems to be a single-pouch model made of hide covered with hair, and, given the maud slung over his shoulder, could not accommodate a blanket.1774, Timothy Pickering describes a single-pouch, double-shoulder-strap leather knapsack being used in the British Army.1776, An American contractor touts his double-pouch, single-shoulder-strap linen “new InventedNapsack and haversack” to Maryland officials. One pouch was meant for food, the other for soldiers’ necessaries. Some Maryland units are known to have been issued the knapsack, and there is some indication it was used by Pennsylvania troops as well.1776-1777, British regiments are issued knapsacks, but many Crown units use blanket slings instead of packs in these two campaigns. (Possibly because the knapsacks then being used could not accommodate a blanket, which were deemed necessary for American service.)1778, The first known image of a double-pouch British knapsack appears in a 71st Regiment order book. One pouch is shown as holding food, the other, soldiers’ necessaries.1778, On 28 July “1096 Knap & Haversacks” (from the context likely the same as the “new Invented Napsack and haversack”) are sent from Reading, Pennsylvania to supply Continental troops.1780, Benjamin Warner was likely issued his double-pouch double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack while serving with a Continental artillery regiment. `1782, First known documentary references to double-pouch knapsacks.1782, L’Enfant painting of West Point showing soldiers with rolled blankets attached to the top of their knapsacks.1794, The earliest known surviving British double-pouch, double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack, made for the 97th Inverness Regiment, raised in 1794 and disbanded the same year.

Footnotes:

- H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, vol. I (Princeton, N.J., 1951), 154-155.

- 84th Regiment order book, Malcolm Fraser Papers, MG 23, K1,Vol 21, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Orderly Book: British Regiment Footguards, New York and New Jersey," a 1st Battalion

Order Book covering August 1776 to January 1777, Early American Orderly Books, 1748-1817, Collections of the New-York Historical Society (Microfilm Edition - Woodbridge, N.J.: Research Publications, Inc.: 1977), reel 3, document 37.

- Sheldon S. Cohen, "Captain William Leslie's 'Paths of Glory,’" New Jersey History, 108 (1990), 63.

- "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" (actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st

Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day the Brigade for American Service was formed), Manuscript Department, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.(Courtesy of Linnea Bass.)

- British Orderly Book [40th Regiment of Foot] April 20, 1777 to August 28, 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 6 (Military Papers, 1755-1798), vol. 1, reel 117. See also, John U. Rees, ed., "`Necessarys

… to be Properley Packd: & Slung in their Blanketts’: Selected Transcriptions 40th Regiment ofFoot Order Book,” http://revwar75.com/library/rees/40th.htm

- "Captured British Orderly Book [49th Regiment], 25 June 1777 to 10 September 1777, . George Washington Papers (microfilm), series 6, vol. 1, reel 117.

- "Orderly Book: First Battalion of Guards, British Army, New York" (covers all but a few days of 1779), Early American Orderly Books, N-YHS (microfilm), reel 6, document 77.

- R. Newsome, ed., "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781", North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX (January-October 1932), no. 2, 178-179; no. 3, 286, 287.

- Order book, 43rd Regiment of Foot (British), 23 May 1781 to 25 August 1781, British Museum, London, Mss. 42,449 (transcription by Gilbert V. Riddle).

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers' food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .