Revisit the best of the blogs from 17th and friends!

Our Officers and Men Behaved Like Men Determined To Be Free

The Battle of Stony Point, Recreated

The night of July 15th, 1779 may have started out as a perfectly normal evening for the roughly 500 British soldiers and 70 women and children stationed at Stony Point. It would erupt into musketry and the clash of steel as American troops would surge over the earthworks.

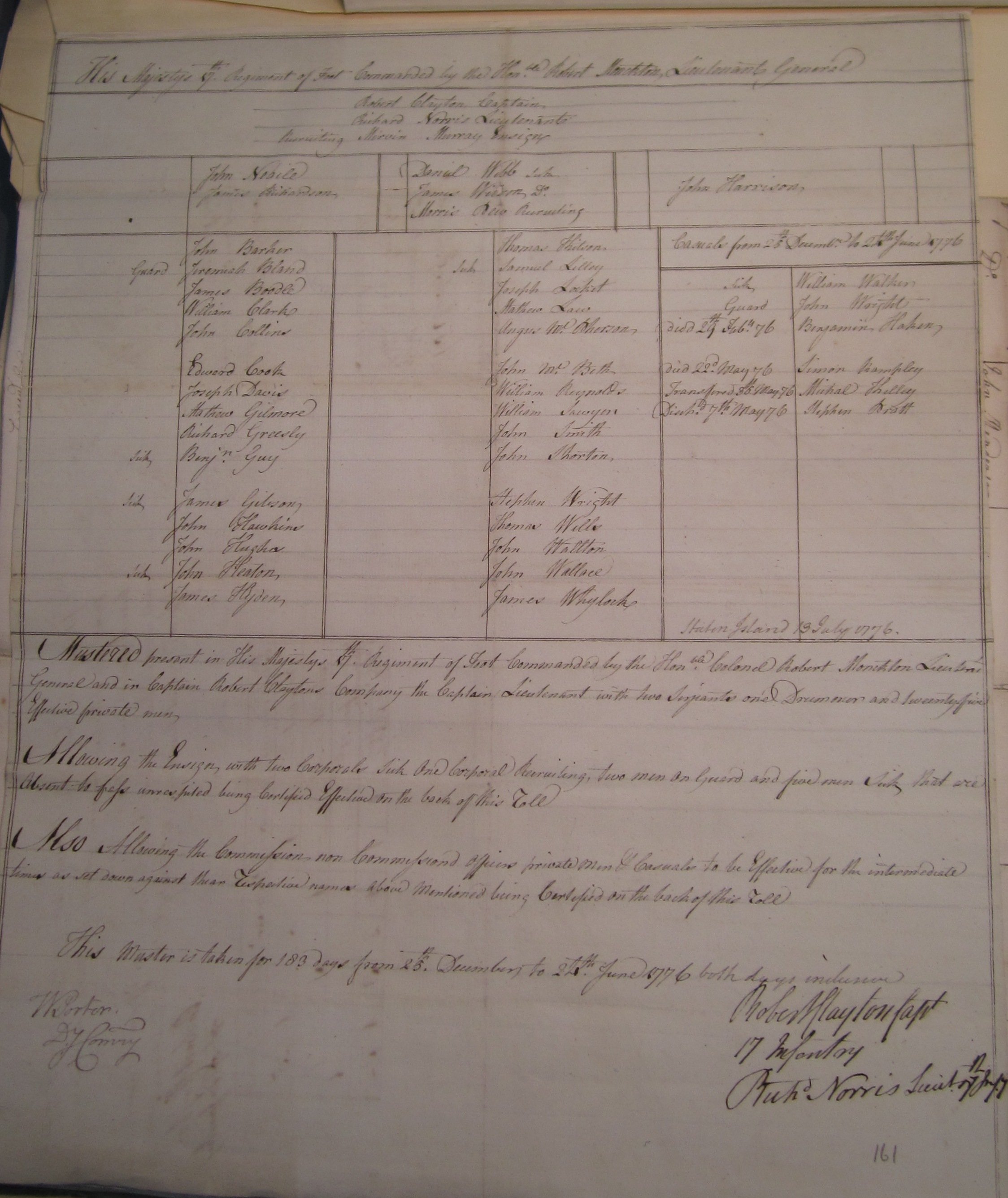

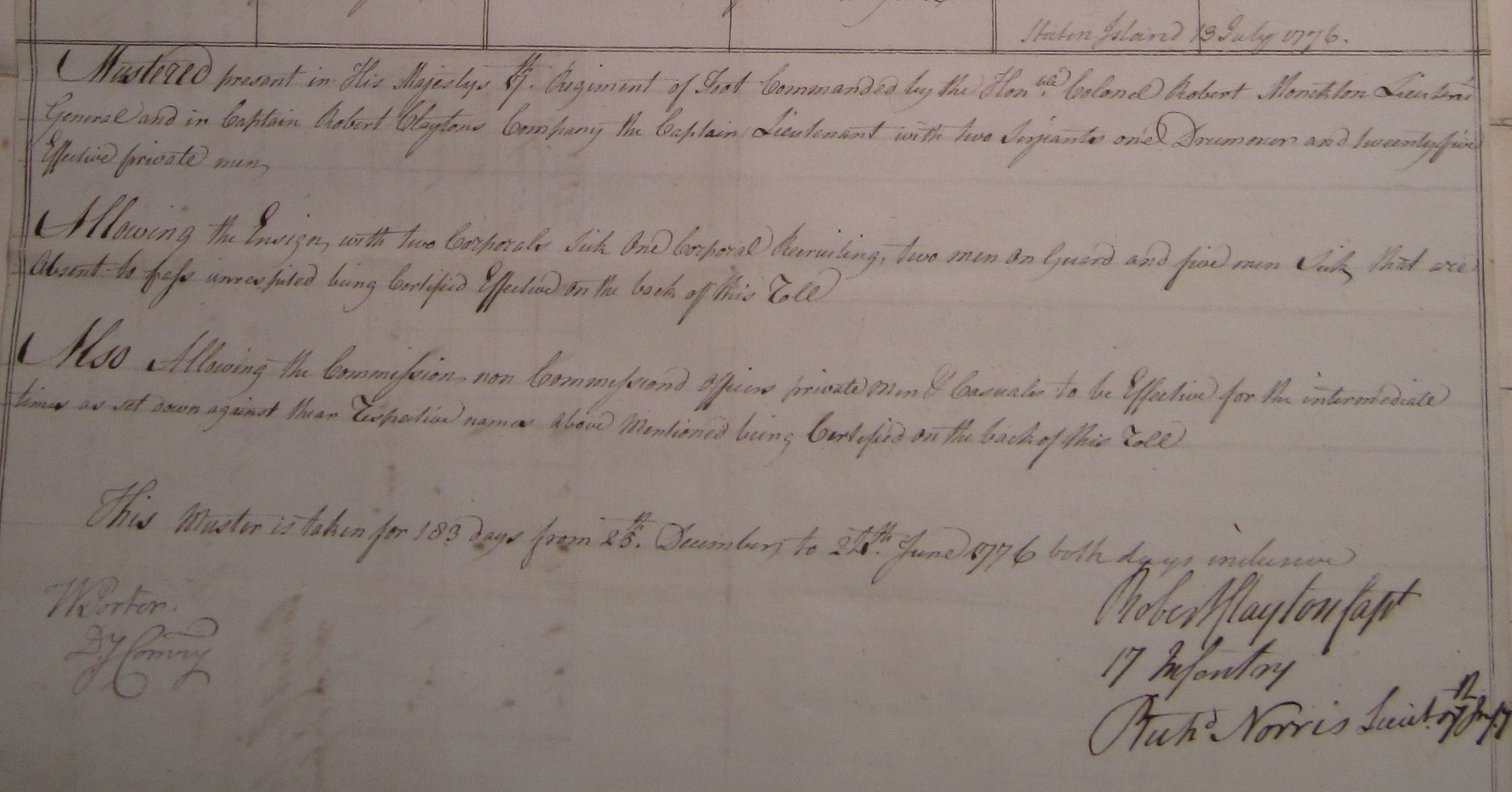

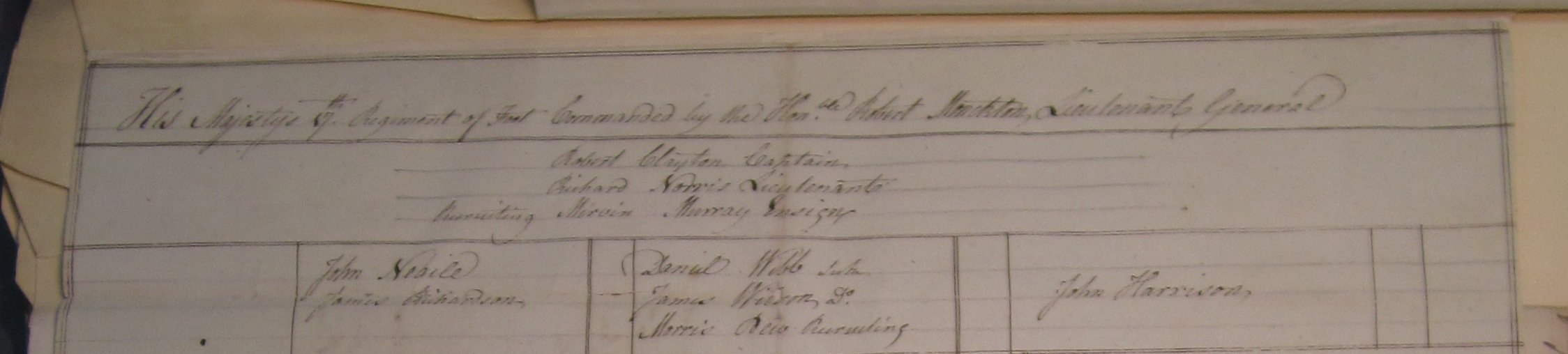

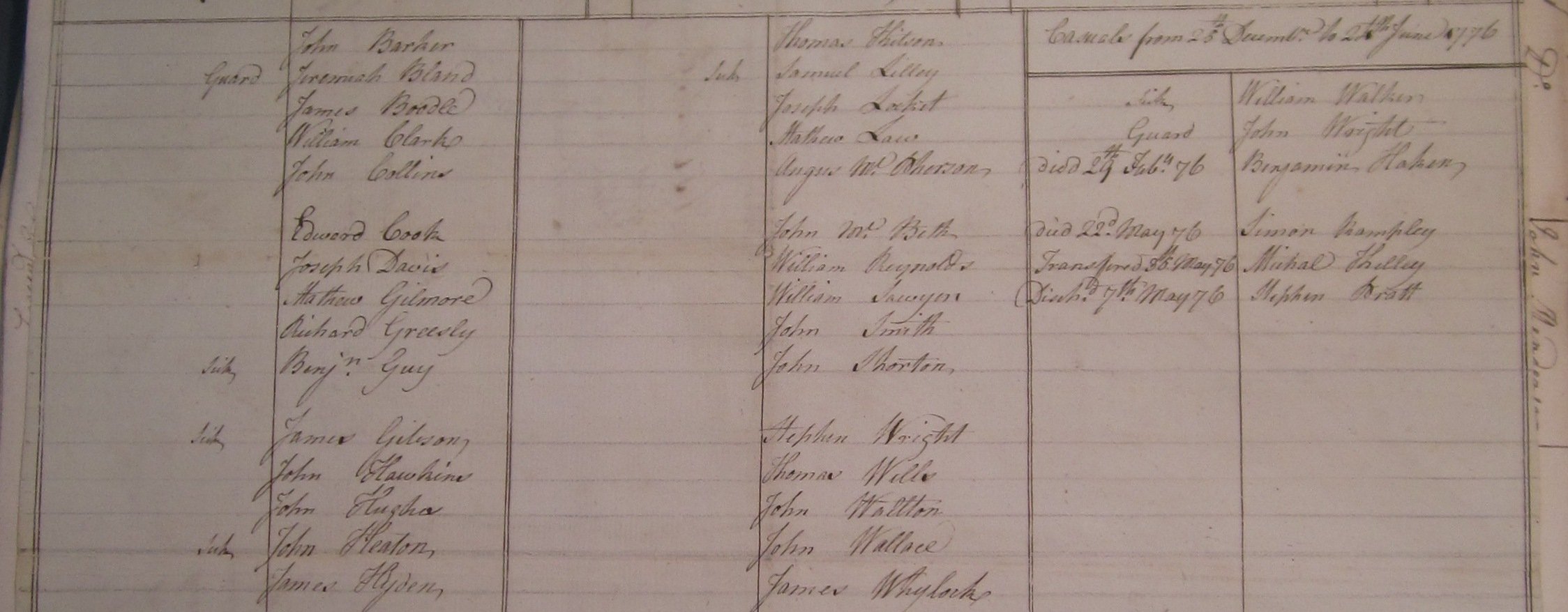

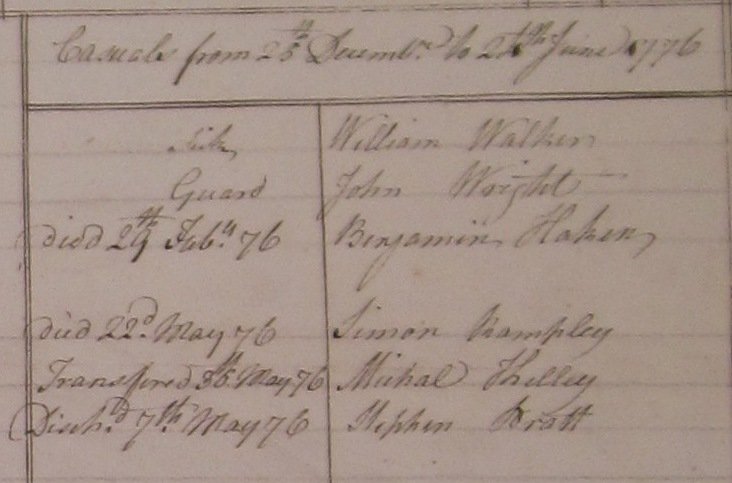

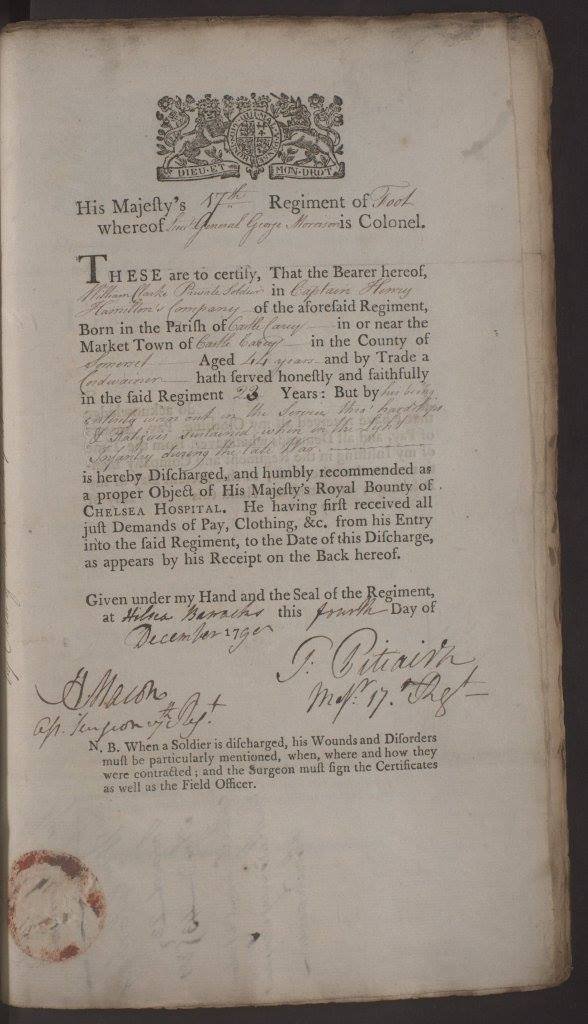

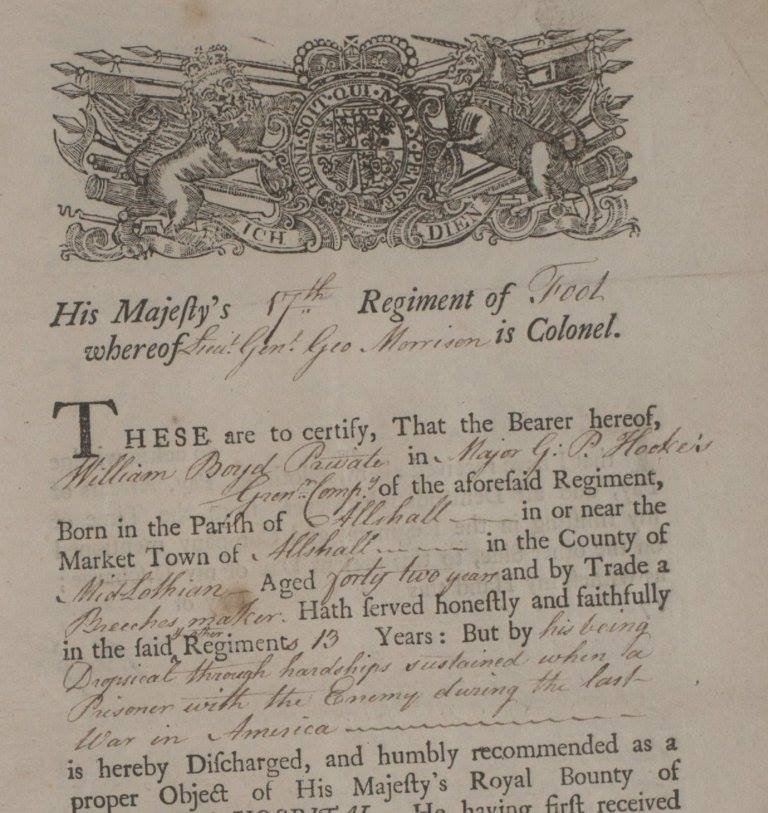

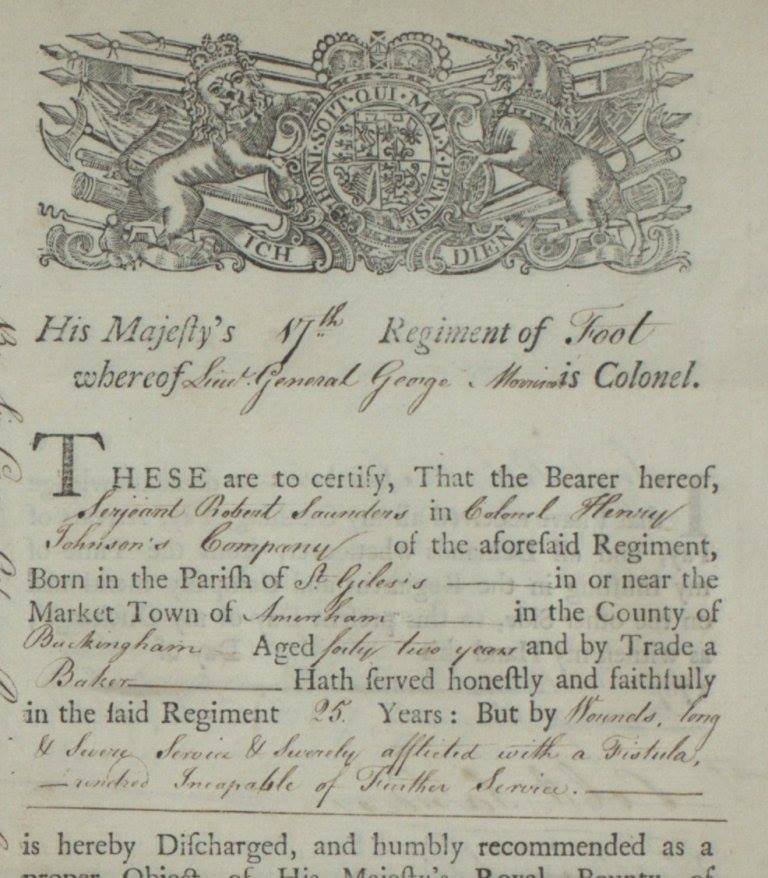

“The works were manned by eight companies of the 17th Regiment of Foot, which had arrived in America in 1775 and were veterans of many of the major battles fought thus far; two companies of grenadiers from the 71st Regiment of Foot (Fraser’s Highlanders), another veteran regiment; sixty-nine men of the Loyal American Regiment, a regiment of Loyalists whose colonel lived twelve miles north of Stony Point; and a number of servants and artisans. In all, the garrison of Stony Point amounted to 564 men.” [2]. These men would be stacked against some of the finest troops the Congressional Army had to throw at them: Anthony Wayne's newly raised Corps of Light Infantry, consisting of four regiments of American troops drawn from all over the States. While the end goal was to secure a vital ferry crossing the Hudson, many consider this battle to be the beginning of the end of the American War of Independence.

The battle was short and brutal. Three columns would carry out the assault: one under the charge of Colonel Butler of Pennsylvania, one with Anthony Wayne, and a third column set out to act as a diversion under the command of Major Hardy Murfree.

Wayne's men set up on the north and south approaches into the post with Murfree in the center with his men. The assault began with Murfree's men firing into the works. The “Forlorn Hope” stormed forth with axes, cleared the abatis, and stormed into the British lines. The columns follow suit, charging forth with bayonets fixed.

As Anthony Wayne led his column up towards the works, he was struck in the head by a musket ball, grazing him but sparing his life. Febiger accepted the surrender on behalf of the American Forces, and the battle is over. [2]

This July we are hoping to recreate what is considered by many to be the “beginning of the end of the American Revolution”. From July 12-14th, American and British reenactors will gather at the Point and try our best to recreate what life might have been like for these men and women.

British forces will have the opportunity to fortify, laying out abatis and wooden fortifications. Women following the army will launder, mend, and ply their trades in the British held position. We hope to recreate what garrison life might have been like for these troops as realistically, accurately, and honorably as possible.

American forces of stout mind and body will be spending Friday a few miles away at Fort Montgomery. They will recreate the night before the assault: mastering the drill, preparing food, and seeing to their laundry and mending rendered by the American followers. Early Saturday morning, the American forces will march along the historical route of march to Stony Point! Fourteen miles through the woods and across the mountains.

The event is shaping up to be one of the best of this year. Reenactors as far west as Iowa, as far north as Maine, and as far south as the Carolinas are coming out to tell the story and bring to life those chaotic days in 1779.

Footnotes:

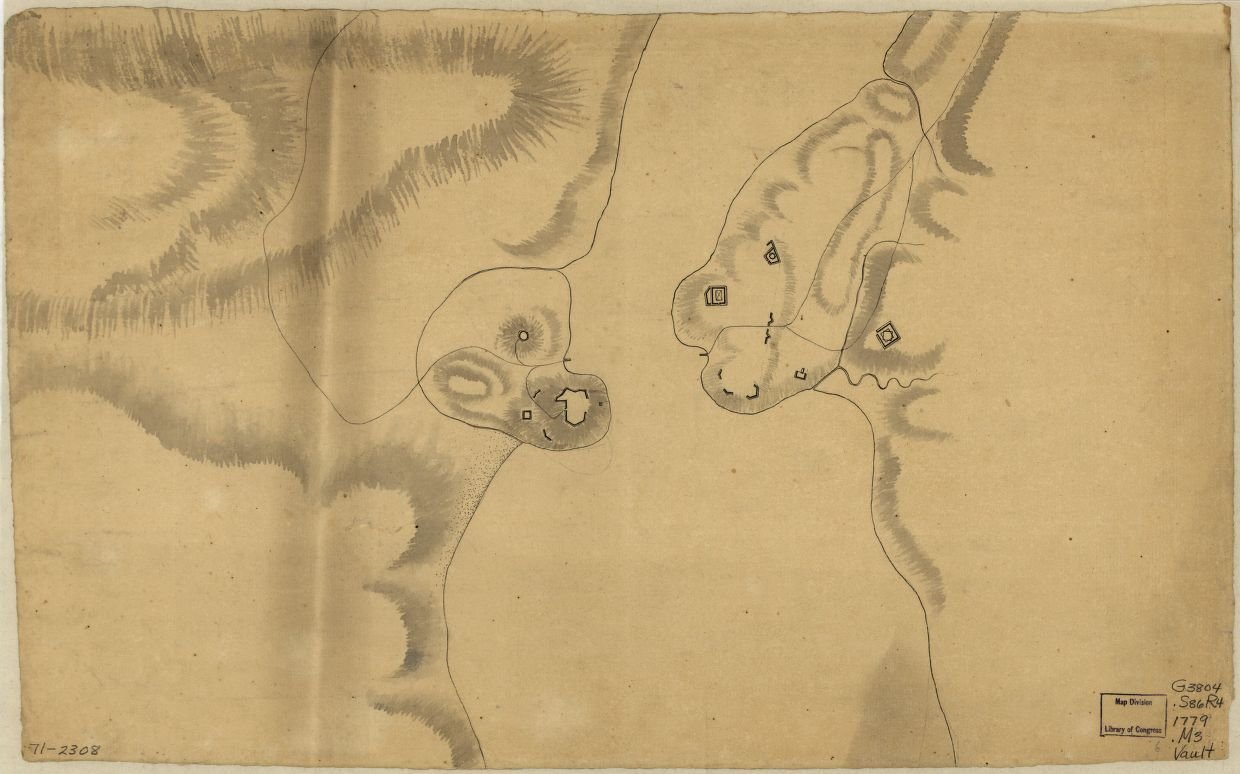

- Map of Stony and Verplanck Points on the Hudson River as fortified by Sir Henry Clinton June. [?, 1779] Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/gm71002308/.

- Anderson, Eric. ""Our Officers and Men Behaved Like Men Determined To Be Free": The Battle of Stony Point, 15-16 July 1779." The Campaign for the National Museum of the United States Army. July 16, 2018. https://armyhistory.org/our-officers-and-men-behaved-like-men-determined-to-be-free-the-battle-of-stony-point-15-16-july-1779/.

- James Peale, Major-General Anthony Wayne, ca. 1795, watercolor on ivory, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Bequest of Mary Elizabeth Spencer, 1999.27.41

HAYDEN CONLEYJoseph Hayden Conley is currently attending Eastern Michigan University, pursuing a BA in Secondary Education History, He is an avid historian, with a particular love of American Light Infantry during the American Revolution and New Jersey troops during the American Revolution. He has worked for Fort Ticonderoga, as well as Mackinac State Historic Parks in Michigan. He has been apart of the living history community for over 10 years, and is a member of the 3rd New Jersey, Captain Bloomfields Company.

HAYDEN CONLEYJoseph Hayden Conley is currently attending Eastern Michigan University, pursuing a BA in Secondary Education History, He is an avid historian, with a particular love of American Light Infantry during the American Revolution and New Jersey troops during the American Revolution. He has worked for Fort Ticonderoga, as well as Mackinac State Historic Parks in Michigan. He has been apart of the living history community for over 10 years, and is a member of the 3rd New Jersey, Captain Bloomfields Company.

Follow-Up: “Like a Pedlar's Pack.”: Blanket Rolls and Slings

Part 3 to A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution Read Parts 1 & 2.

“Square knapsacks are most convenient …”

While British troops used blanket slings instead of knapsacks during several campaigns, one reason being the “ill Conveniency” of their packs (whatever that might mean), slung blankets had their own inconveniences, one of those being having to undo them every night and re-roll them before marching. Here we have American surgeon Dr. Benjamin Rush’s observations while tending to American wounded after the Battle of Brandywine:

One of the [British] officers, a subaltern, observed to me that his soldiers were infants that required constant attendance, and said as a proof of it that although they had blankets tied to their backs, yet such was their laziness that they would sleep in the dew and cold without them rather than have the trouble of untying and opening them. He said his business every night before he slept was to see that no soldier in his company laid down without a blanket."1

Welbourne Immersion Event 2015

Welbourne Immersion Event 2015

That said, British troops certainly used slings, and likely used rolled blankets slung over the shoulder, as well (see image of 25th Regiment soldier at Minorca, below). Here are a series of British narratives or general orders mentioning blanket slings, or occasions when blankets were to be carried without knapsacks.

84th Regiment, “point au Trimble,” Quebec, 18 August 1776, "Every Man to be pervided With a Topline [tumpline] if Wanted and to prade Opisite the Church, on Thursday Morning With thire Arms Accutements and packs, properly Made up as for a March.”2

Brigade of Guards, orders, 19 August 1776, "When the Brigade disembarks two Gills of Rum at most must be put into each Man's Canteen which must be fill'd up with Water. Every Man is to disembark with a Blanket, in which he is to carry three days provisions, one Shirt, one pair of Socks, & one pair of Shoes. A careful Man to be left on Board each Ship to take care of the Mens Knapsacks, if there are any Convalescents they may be order'd for this.”3

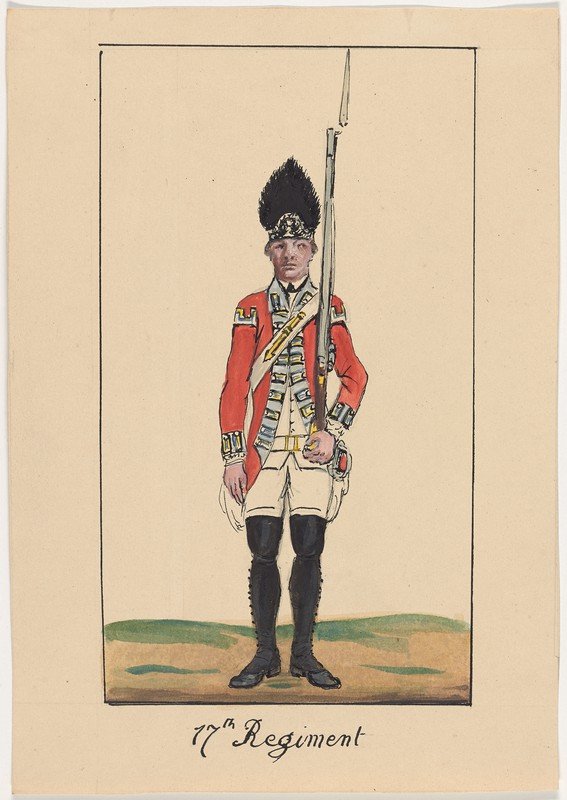

Capt. William Leslie, 17th Regiment of Foot, 2 September 1776, “"Bedford Long Island Sept. 2nd 1776… The Day after their Retreat we had orders to march to the ground we are now encamped upon, near the Village of Bedford: It is now a fortnight we have lain upon the ground wrapt in our Blankets, and thank God who supports us when we stand most in need, I have never enjoyed better health in my Life. My whole stock consists of two shirts 2 pr of shoes, 2 Handkerchiefs half of which I use, the other half I carry in my Blanket, like a Pedlar's Pack."4

Brigade of Guards, orders, 11 March 1777, "The Waistbelts to Carry the Bayonet & to be wore across the Shoulder. The Captains are desired to provide Webbing for Carrying the Mens Blankets according to a pattern to be Seen at the Cantonment of Lt. Colo. Sr. J. Wrottesleys Company. The Serjeants to Observe how they are Sewed. The Officers to Mount Guard with their Fuzees."5

40th Regiment orders regarding blanket slings, wallets, and contents, spring and summer 1777:6 After Regl Orders 7 at Night [10 May 1777]

A Return to be given immediatly from each Company to the Qr. Mr. of the Number of Shoe soles and heels wanting to Compleat each man with a pair to take with him the Ensuing Campaign

The Regt. to parade to morrow Morning at 11 oClock with Arms, Accoutrements & Necessarys in order to be inspected by their Officers -- The Necessarys to be carried in their Wallet and slung over the Right Shoulder --

R[egimental]:O[rders] 14th May 1777

Each Compy. will immediately receive from the Qr. Mr. Serjt. 26 Slings & Wallets to put the quantity of Necesareys Intendd. to be Carrid. to the field Viz 2 shirts 1 pr. of shoes & soles 1 pr. of stockings 1 pr. of socks shoe Brushes, black ball &c Exclusive of the Necessareys they may have on (the[y] must be packd. in the snugest manner & the Blankts. done neatly round very little longer than the Wallets) to be Tyed. very close with the slings and near the end -- the men that are not provided. with A blankett of their own may make use of one [of] the Cleanest Barrick Blanketts for to morrow –

After Regl. Orders 7 at Night [18 May 1777] …

The Regt: to parade to morrow Morning at 11 oClock with Arms, Accoutrements & Necessarys in order to be inspected by their Officers – The Necessarys to be carried in their Wallet and slung over the Right Shoulder … The pipe Clay brought this day from Staten Island to be divided in eight equal parts and each Company to get a dividend it is hoped the Compys: will make better use of this then thay did of the last

[Regimental Orders, 23 May 1777] … The Non Commissd: Offrs: and Men to have their Necessareys Constantly packd: in their Wallets ready to sling in their Blanketts which they are to parade with Every morning at troop beating to Acustom them to do it with Readiness and Dispatch The men of the Qr:Gd: to parade when the taps beat to be properly inspectd: and ready to march of[f] Immediately fter the troop has beat –Morn.g Regl. Orders 2d June 77 …

Black tape to be provided immediately to tie the Mens Hair -- NB It is to be had in Amboy. -- The Mens Hair that is not properly Cut to be done this Day -- Each Company to give in a Return to the Quarr. Masr. of the Number of Wallets & Slings wanting to Compleat each Man as the whole must have them to appear uniform in the slinging on & Carrying their Blankets & Necessarys -- Any of the Wallets or Slings not properly made to be returned to the Masr. Taylor –

R[egimental]:O[rders] [9 June 1777] …

The Commanding Offrs: of Comp[anie]s. are Immediately to settle their Accompts With the Qr: Mr: for the under Mentiond Articles According to the following rates at 4 [shillings]:8d pr Doller

Trowzrs: making &c ....................... £ 4:2 1/2Wallets & Slings. ......................... 2:2 1/2Coats Cuting & Mending when at Hallafax..... 4 1/2Do: Do: at Amboy .......................... 10Diffeichinceis on Breeches clothwhen at Staten Island. ................ 4 1/2 Do: on Leggons ............................. 349th Foot, "Regimental Order on Board the Rochford 21 August 1777 When the Regt. Lands

Every Non Commissd Officer and soldier of the Regiment is to have with him 2 very good Shirts, Stokings, 2 pair Shoes, their Linin drawers, Linnin Leggins, half Gaiters and their Blankets very well Rold. Every thing to be perfectly Clean. Officers Commanding Companies will be answerable to the Commanding Officer that these orders are Strictly Complyed with-“7

Guards, “Brigade Morning Orders 30 August 1779 The Qr. Masters are desir'd to be as expeditious as possible in processing proper Bedding &ca from the Bk. Mr. Genl.-- & Field Blankets from the Qr. Mr. Genl. for the Draughts received from England.-- & to deliver to them from the Regl. Store a proper proportion of Camp Kettles, Canteens & Haversacks.The Companies are desir'd to Compt. their Draughts with proper Straps to Carry their Blankets, & to be as expeditious as possible in Compleating them with Trowsers."8Brigade of Guards, “1st Battn Orders 9 September 1779 The Men lately Joind having received their Field Blankets, the Serjts. are Ordered, to see that they are Mark'd with the Initial Letters of each Mans Name. The Men are to be provided with proper Straps for Carrying them & Shewn how to Roll them up.9

Lt. Gen. Charles Earl Cornwallis’s army, South Carolina, 1780 and 1781:10

On board ship off of Charlestown, South Carolina, 15 December 1780.General orders:

"The Corps to Compt. their Men with Camp Hatchets Canteens, & Kettles ... It is recommended to the Comdg Offrs. of Regts. to provide the Men with Night Caps before they take the Field."

Brigade orders:

"The Necessaries of the Brigde. are to be Imdy. Comptd. to 2 Good pr. Shoes, 2 Shts. & 2 pr. Worsted Stockgs. per Man ... Each Mess to be furnish'd with a Good Camp Kettle, & every Man provided with a Canteen, & Tomahawk - & the Pioneers wth. all kind of Tools. The drumrs. are to carry a good Ax Each & provide themselves with Slings for the Same."

General orders, Ramsour's Mills, 24 January 1781:

"When upon any Occasion the Troops may be Order'd to March without their Packs; it is not intended they Should leave their Camp Kettles and Tomahawks behind them."

Brigade orders, 24 January 1781:

"There being a Sufficient Quantity of Leather to Compleat the Brigade in Shoes ... It is recommended to ... the Commandg. Officers of Companies, see their Mens Shoes immediately Soled & Repaired, & if possible that every Man when they move from this Ground take in his Blankett one pair of Spare Soles ..."

43rd Regiment, Virginia,"Apollo Transport Of[f] Brandon James River 23rd May 1781 …The Quarter Master will issue Canteens Haversacks and Camp Kettles to the Battalion immediately. The Companies to send Returns for their Effectives as this is the only supply the Regiment can possible Receive during the Campaign the Soldiers cannot be to careful to preserve them.Five Regimental Waggons will land with the Regiment. One to each Grand Division the fifth for Major Fergusons Baggage.The Quarter Master will issue an equal proportion of the Trowzers, made since the Embarkation- to each Company to compleat them as near as possible to Two pair per Man.It is positively Ordered that no Soldier lands with more necessaries than his Blanket, Canteen,Haversack, Two pair of Trowzers, Two pair of Stockings, and Two Shirts, and Two pair of good Shoes. The Remaining Necessaries of each Company to be carefully packed up and Orders will be given as soon as possible for its been taken proper care of."11

Footnotes:

- H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, vol. I (Princeton, N.J., 1951), 154-155.

- 84th Regiment order book, Malcolm Fraser Papers, MG 23, K1,Vol 21, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Orderly Book: British Regiment Footguards, New York and New Jersey," a 1st Battalion

Order Book covering August 1776 to January 1777, Early American Orderly Books, 1748-1817, Collections of the New-York Historical Society (Microfilm Edition - Woodbridge, N.J.: Research Publications, Inc.: 1977), reel 3, document 37.

- Sheldon S. Cohen, "Captain William Leslie's 'Paths of Glory,’" New Jersey History, 108 (1990), 63.

- "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" (actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st

Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day the Brigade for American Service was formed), Manuscript Department, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.(Courtesy of Linnea Bass.)

- British Orderly Book [40th Regiment of Foot] April 20, 1777 to August 28, 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 6 (Military Papers, 1755-1798), vol. 1, reel 117. See also, John U. Rees, ed., "`Necessarys

… to be Properley Packd: & Slung in their Blanketts’: Selected Transcriptions 40th Regiment ofFoot Order Book,” http://revwar75.com/library/rees/40th.htm

- "Captured British Orderly Book [49th Regiment], 25 June 1777 to 10 September 1777, . George Washington Papers (microfilm), series 6, vol. 1, reel 117.

- "Orderly Book: First Battalion of Guards, British Army, New York" (covers all but a few days of 1779), Early American Orderly Books, N-YHS (microfilm), reel 6, document 77.

- Ibid.

- R. Newsome, ed., "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781", North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX (January-October 1932), no. 2, 178-179; no. 3, 286, 287.

- Order book, 43rd Regiment of Foot (British), 23 May 1781 to 25 August 1781, British Museum, London, Mss. 42,449 (transcription by Gilbert V. Riddle).

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .

A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution part 2

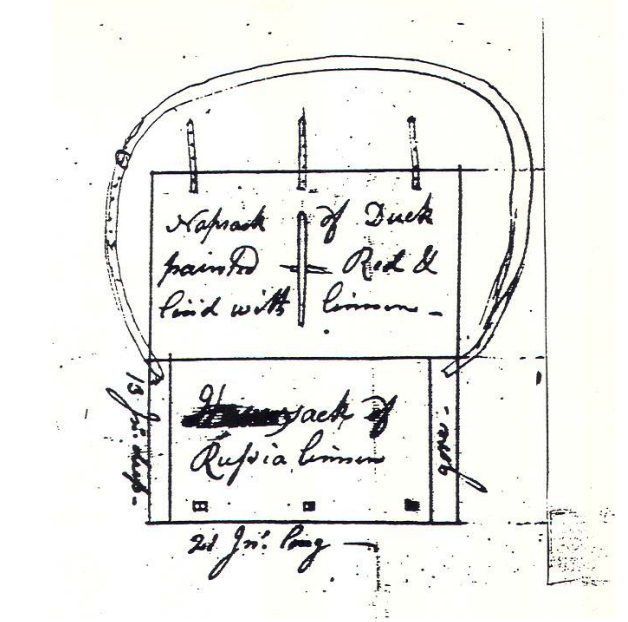

While we may never learn the answers to the aforesaid questions, here are several things we do know or think we know. First, we look at a crucial clue in this discussion, but one that is accompanied with some uncertainty and a caveat or two. The first known image of a British double-pouch knapsack (see below) was found in a 71st Regiment manuscript book titled “Standing Regimental Orders in America”; the first half of the volume contains standing orders for 1775 (before the regiment arrived in North America), the second half entries for 1778, beginning 3 June and ending with a 24 August order. The context of the knapsack image is difficult to ascertain but, in my opinion, was likely done in 1778. A caveat – while we can assume it portrays a piece of British equipment, the possibility of the image showing a captured item remains in the realm of possibility. That possibility seems to be lessened by the absence of a descriptor noting such. Added to that, there are indications the British went into the war using single-pouch knapsacks, the 71st order book drawing, likely dating to 1778, being the earliest evidence for the double-pouch variety.

Next, a known item with a supposition attached to it. In February 1776 a contractor sent a proposal to convince the state of Maryland to procure for their troops his “new Invented Napsack and haversack.” In the end numbers of his knapsack were made and issued to several Maryland units, and probably some Pennsylvania and New Jersey troops. Though impossible to prove, an intriguing possibility is that the new British knapsacks were inspired by the American “Napsack and haversack,” a not unreasonable contention given the similarity in design and that the 71st knapsack drawing also shows one pouch designated to carry food.

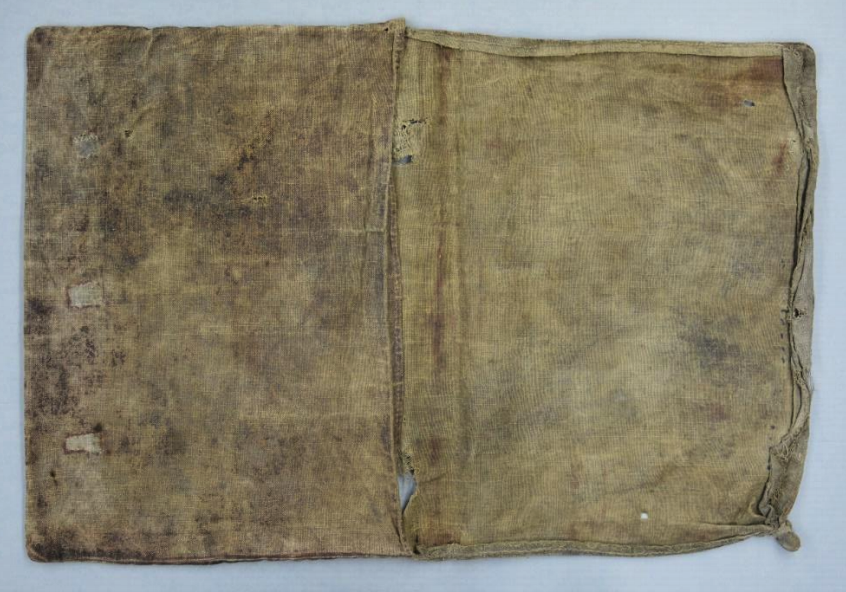

From 1776, we move four years ahead, to Benjamin Warner’s service with Col. John Lamb’s 2d Continental Artillery Regiment. Given that his other tours, from 1775 to 1777, were with state or militia units, and given what we know of America knapsacks during those years, it is most likely his extant knapsack dates from his 1780 stint. Warner’s pack may have been copied from captured British equipment. The practice did occur, perhaps the best known instance being the Continental Army twenty-nine round “New Model” cartridge pouch, copied from British pouches taken with Burgoyne’s troops and first made in Massachusetts in the winter of 1777-78.

(See following page for images of the Warner knapsack.)

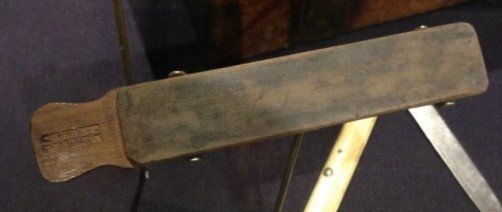

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack.

(Above) Benjamin Warner's Revolutionary War knapsack. This artifact has evidence a second pocket on the inside of the outer flap. (Courtesy of Fort Ticonderoga Museum) (Below) Reproduction of Warner knapsack. While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

While Benjamin Warner’s existing knapsack is evidence that the Continental Army used doublepouch knapsacks with two shoulder straps by at least 1780, the first documentary mentions date to 1782.Quartermaster General Timothy Pickering to Ralph Pomeroy, D.Q.M., 23 April 1782:

"I observe in your return the mention of upwards of three thousand yards of oznaburghs Tho' this kind of linen is not the best for knapsacks yet they have very commonly been made of it. Of that in your possession I wish you to select immediately the best, & to have one thousand knapsacks made up. They should be made double, & one side painted with the cheapest paints. I will furnish you with Mr. Morris's notes to enable you to pay for this work which cannot cost much. Be pleased to have the knapsacks made with dispatch & forwarded without delay to Colo. Hughes."

Numbered Record Books, National Archives, 1780-July 9, 1787, vol. 26.Timothy Pickering to Peter Anspach, 23 April 1782:

"Desire Mr. [Mery?] to examine the bolts of oznaburghs which came from Virginia, and pick out those fittest for knapsacks, & get as many made as he can: If he would cut out one of a proper shape, he could get some careful woman to cut out the residue, & employ other women to make them up. Let them be made double, & one side painted. Perhaps all the oznaburghs will answer as well as those knapsacks usually made. There are some here which were left or rather contracted for by Col. Mitchel, that are wretched indeed: I think any of our oznaburghs better by far."

Miscellaneous Numbered Records (The Manuscript File) in the War Department Collection of Revolutionary War Records 1775–1790's, National Archives Microfilm Publication M859, (Washington, D.C., 1971), reel 87, item no. 25353.

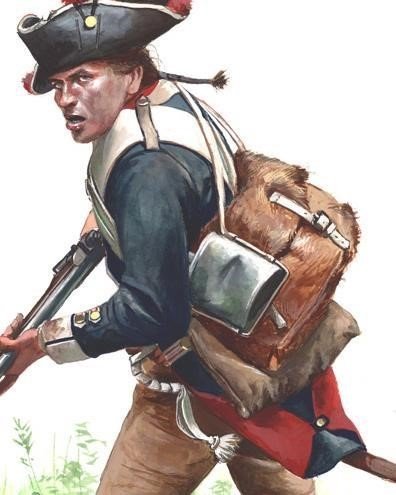

Also in 1782, Pierre L’Enfant, captain Corps of Engineers, painted a panorama of West Point. To one side are two groups of Continental troops, including several soldiers wearing rolled blankets atop their knapsacks, the first images showing that being done.

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"]

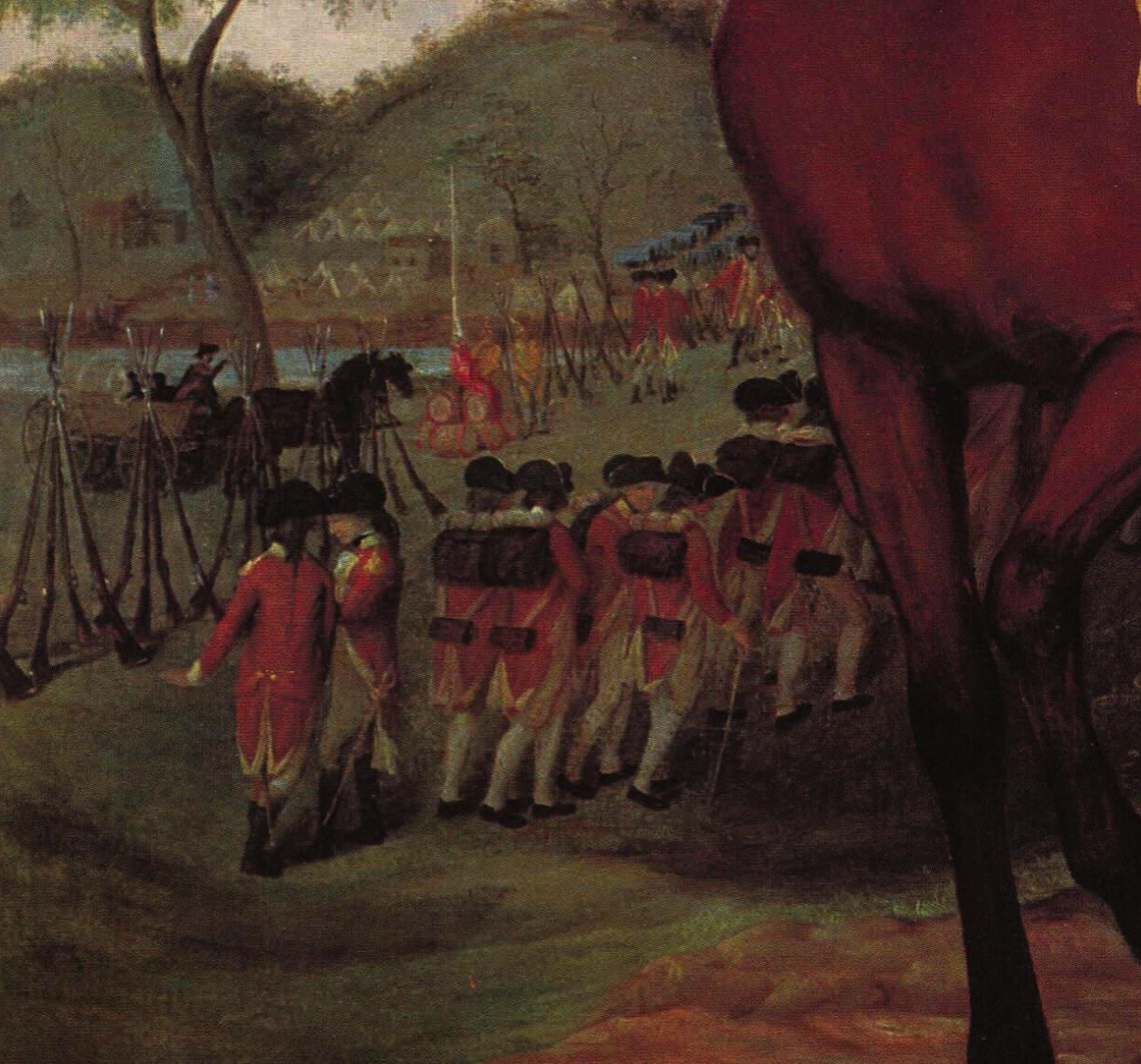

[gallery ids="3826,3825" columns="2" size="full"] Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Another painting shows British troops, after their surrender at Saratoga in October 1777, with rolled blankets attached to their knapsacks. Unfortunately, the painter, James Peale, was not an eyewitness, and executed the image in 1799 or 1800.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

Rounding out this discussion, we close with images of the earliest known surviving British double-pouch knapsack, dated to 1794 and attributed to the 97th Inverness Regiment.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers’ food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .Read Part 1 of A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution Here !

A Hypothesis Regarding British Knapsack Evolution

“Square knapsacks are most convenient …”

This post began with the vague idea of discussing the 17th Regiment’s recreated knapsack. To my mind it is the only one that comes close to representing the design of the originals likely carried by mid-war (and possibly late-war) British soldiers. But that set me to ruminating on how the double-pouch knapsack (such as the Benjamin Warner pack at Fort Ticonderoga and the one pictured below in the 71st Regiment’s 1778 order book) came to be. The following narrative, based on both primary and, admittedly, circumstantial evidence, attempts to trace that transformation, and (spoiler alert) leads the author to think it very likely the double-pouch pack was a wartime innovation.

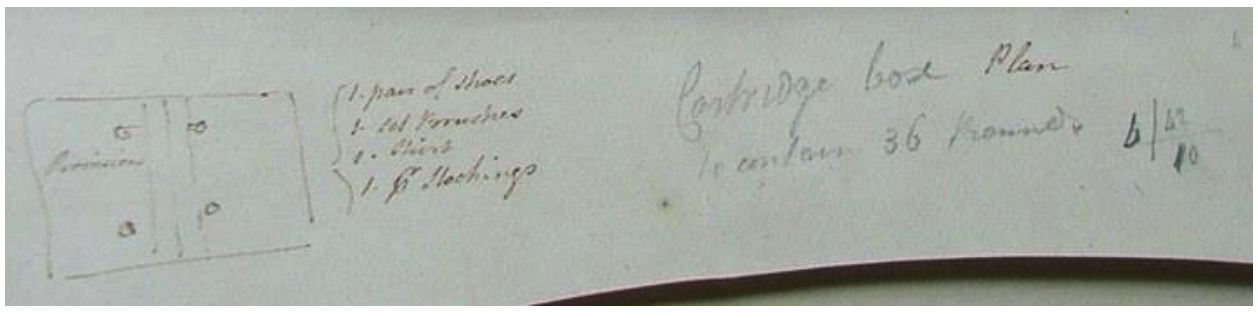

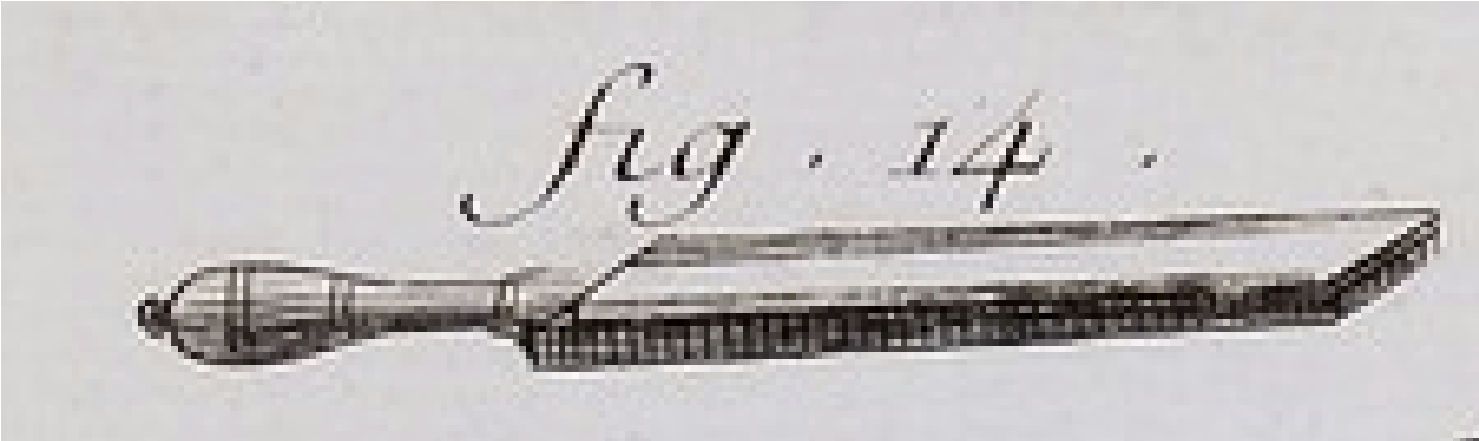

Drawing of knapsack from British 71st Regiment 1778 order book. This is likely evidence that double-bag knapsacks, undoubtedly of linen, were being used by British troops at least by 1778. Note that food was to be carried in one bag, and a minimum of necessaries (“1 pair of shoes,” “1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt, “1 Pr. stockings”) in the other. Continental Army twoshoulder-strap double-bag packs were probably copied from British knapsacks. The Warner knapsack (probably issued in 1779) had two storage pouches; orders for American army knapsacks in 1782 stipulated, “Let them be made double, & one side painted.” Standing Orders of the 71st Regiment, 1778, Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell, National Register of Archives for Scotland (NRAS 28 papers), Isle of Canna, Scotland, U.K.(Knapsack drawing courtesy of Alexander John Good.)51

[gallery ids="3610,3619" columns="2" link="file" size="full"]Recreated Knapsacks, 17th Regiment

There are occasions (actually, many occasions) when my understanding runs on a very slow burn. In this vein, researching and writing about knapsacks used before, during and after the American War (1775-1783), eventually led me to the conclusion that British knapsack design took a right turn early in that conflict. Is my conclusion conclusive? No, it isn’t, as there are missing pieces in the records, but the possibility (or probability) is intriguing.

* * * * * *In his 1768 treatise System for the Compleat Interior Management and Oeconomy of a Battalion of Infantry Bennett Cuthbertson wrote,

Square knapsacks are most convenient, for packing up the Soldier’s necessaries, and should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen: a certain size must be determined on for the whole, and it will have a pleasing effect upon a March, if care has been taken, to get them of all white goat-skins, with leather-slings well whitened, to hang over each shoulder; which method makes the carriage of the Knapsack much easier, than across the breast, and by no means so heating.9

Cuthbertson reveals here several notable clues. First, of course, is his statement touting the superiority of “square” knapsacks with two shoulder slings. The 1751 Morier figures and the circa 1765 painting “An Officer Giving Alms to a Sick Soldier” by Edward Penny (1714-1791) show soldiers wearing single-shoulder-strap skin packs, so Cuthbertson’s square knapsack was a relatively recent innovation. Mr. C. also states square packs “should be made with a division, to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen” and “a certain size must be determined on for the whole …” ”[M]ade with a division.” That, to me, indicates Cuthbertson is speaking of a single pouch knapsack, like the David Uhl and Elisha Grose packs, while his remark about determining size can only mean no standard design had yet been settled on. And his reference to “all white goat-skins” refers to a knapsack likely made entirely of leather, again like the Grose knapsack. Both pre-war and in the war’s early years leather seems to have been the preferred material for many, perhaps most, knapsacks.

(For references to leather packs see sections titled “Leather and Hair Packs, and Ezra Tilden’s Narrative” and “The Rufus Lincoln and Elisha

Gross Hair Knapsacks” in “’Cost of a Knapsack complete …’: `This Napsack I carryd through the war of the Revolution,” Knapsacks Used by the Soldiers during the War for American Independence’” http://www.scribd.com/doc/210794759/%E2%80%9C-This-Napsack-I-carryd-through-the-war-of-theRevolution-Knapsacks-Used-by-the-Soldiers-during-the-War-for-American-Independence-Part-1-of-

%E2%80%9C-Cos ; see also, Al Saguto, “The Seventeenth Century Snapsack” (January 1989) http://www.scribd.com/doc/212328948/Al-Saguto-The-Seventeenth-Century-Snapsack-January-1989 )

[gallery ids="3628,3638" columns="2" size="full"]Detail from David Morier, “Grenadiers, 46th, 47th and 48th Regiments of Foot, 1751” http://www.royalcollection.org.uk/collection-search/david%2520morier

Based on the writing of Massachusetts militia colonel Timothy Pickering (below), sometime prior to 1774, packs like the one Cuthbertson described seem to have been adopted by at least some British regiments:

A knapsack may be contrived that a man may load and fire, in case of necessity, without throwing down his pack. Let the knapsack lay lengthways upon the back: from each side at the top let a strap come over the shoulders, go under the arms, and be fastened about half way down the knapsack. Secure these shoulder straps in their places by two other straps which are to go across and buckle before the middle of the breast. The mouth of the knapsack is at the top, and is covered by a flap made like the flap of saddlebags.- The outside of the knapsack should be fuller than the other which lies next to your back; and of course must be sewed in gathers at the bottom. Many of the knapsacks used in the army are, I believe, in this fashion, though made of some kind of skins.20

Pickering, too, refers to packs made of leather, infers that they had only a single pouch, and adds that the closing flap resembles those on saddle bags of the time. Period examples have closing flaps similar to those on the Uhl (linen) and Grose (bearskin) knapsacks.

So, just when were double-pouch knapsacks (like Benjamin Warner’s 1780 pack) first introduced to British troops in America? A drawing from a 1778 71st Regiment order book found and shared by Alexander John Good may provide the answer. That image shows a very simple double-pouch knapsack, with food placed in one pouch and “1 pair of shoes,” 1 set Brushes,” “1 shirt,” and “1 pr stockings” in the other. (It is interesting that this apportionment mirrors that of the “new Invented Napsack and haversack” used by some Whig units in 1776, 1778, and possibly 1777, but more on that later).

See the timeline of British Knapsacks at the bottom of this article.

British regiments already in America at the beginning of the war had knapsacks, but we have no idea of their design. At this time, given what we know of pre-war packs from period images and the comments of Cuthbertson and Pickering, I can only surmise that early-war (1775-1777) British knapsacks were leather (goatskin?), possibly linen, “square” models, with a single pouch (possibly with a divider to separate a spare pair of shoes from the other necessaries), and two shoulder straps. They also could not easily accommodate a blanket, an item deemed necessary for service in North America. British, French, and German troops campaigning in Europe did not carry blankets on the march, those coverings being carried in the same wagons as the regimental tentage. The packs (tournisters) German troops carried while serving in the American War still could not carry a blanket, and we are still unsure how, or even if, German troops carried blankets on the march.

Supply documents for the British Brigade of Guards, 1776 to 1778, including numbers of knapsacks issued and the use of blanket slings on campaign, and generate some interesting questions.

[Numbers of knapsacks needed and requested]

List of Waggons, Tents, Camp necessaries &ca for the Detachment from the Three Regiments of Foot Guards, consisting with their Officers of 1097 men destined to Serve in North America.

February 5th 1776 …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks(Loudoun p.213) (see also WO4/96 p.45 7 Feb. 1776 Barrington to Loudoun)[Knapsack pattern]Memo Brig. Gen. Edward Mathew to John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun 16 Feb. 1776 "Memorandum concerning the [Guards] Detachment Fryday Feb 16 1776" "Light Infantry Company. Colo. Mathews applies for the proper Clothing.proposes: To cut the 2nd Clothing of this Year into Jackets. --Caps, Colo. M to produce a pattern --Arms, The Ordnance will deliver them with the others. a fresh Application.Accoutrements, upon the plan of the light Infantry. Colo. M--Bill Hook and Bayonet in the same case. Colo M.-- ""Gaiters and Leggins Knapsack -- Genl. Tayler has a pattern. Nightcaps -- Colo. M to shew one Canteens -- to see a Wooden one."(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6510)[Altering knapsacks] Memo Mathew to Loudoun 28 Feb. 1776

"Estimate of the Extra expence of the Necessary Equipment of the Detachment from the Brigd. of Foot Guards Intended for Foreign Service"

Alteration of the Mens Knapsacks .6 [pence]To Receive from the Goverment in Lieu of Knapsacks 2.6Allowance from Govermt. to each Man for a Knapsack 2.6(Loudoun-Hunt. LO 6514)[Fitting knapsacks] Regimental Order, London 7 March 1776The 1st Regt. will draught the 15 men "by Lot out of such Men as are in every respect fit for Service."2nd and 3rd Battalion to draught Sat the 9th 1st Battalion on Sun the 10thA return to be sent in of the name, age and service of the men. Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

Commanding Officers of companies "will Inspect minutely into the Men's Necessaries who are Draughted, that they may be Compleated according to the List to be seen at the Orderly Room, The Knapsacks to be fitted to each Man, according to a late Regulation, and to be seen that they are perfectly whole and strongly sewed."

"The Extraordinary necessaries furnish'd are not to be deliver'd to the Men till they are in their first Cantonments."

(First Guards)[List of soldiers’ necessaries, including knapsacks] Brigade Orders, London 13 March 1776"The Necessarys of the Detachment are to be Compleated to the following Articles -- Three ShirtsThree Pair worsted StockingsTwo pair of Socks 7/ 1/4 pr. PairTwo pair of ShoesThree pair of Heels and Soles 1/2 d pr. pairTwo Black StocksTwo Pair of Half Gaiters 1s/ pr. pairOne Cheque Shirt 3/9 dA Knapsack (2/6 d Allowed by Government)Picker, Worm & TurnscrewA Night Cap"(Scots)

A little over a month later, on 26 April 1776, the three Guards Battalions set sail for North America.

With all the trouble taken to procure knapsacks for the Guards Brigade, those packs seem to have either been left aboard the transports when the Guards went ashore at Long Island, New York or sent back on board after landing. Several 1776 documents mention knapsacks or the lack thereof during the New York campaign.

"[Guards] Brigade Orders August 19th [1776.]When the Brigade disembarks two Gils of Rum to be delivered for each mans Canteen which must be filled with Water, Each Man to disembark with a Blanket & Haversack in which he is to carry one Shirt one pair of Socks and Three Days Provisions a careful Man to be left on board each Ship to take care of the Knapsacks. The Articles of War to be read to the Men by an Officer of each Ship."(Thomas Glyn, "The Journal of Ensign Thomas Glyn, 1st Regiment of Foot Guards on theAmerican Service with the Brigade of Guards 1776-1777," 7. Transcription courtesy of Linnea M. Bass.)General (Army) Orders 20 August 1776"When the Troops land they are to carry nothing with them but their Arms, Ammunition, Blankets, & three Days provisions. The Commandg. Officers of Compys. will take particular care that the Canteens are properly fill'd with Rum & Water & it is most earnestly reecommended to the Men to be as saving as possible of their Grog." (1) (2)Brigade Orders 23 August 1776 [the day after their landing on Long Island]"the Brigade will Assemble with their Arms Accoutrements Blankets & Knapsacks to Morrow Morning at 5 oClock upon the same ground. . ." (2) (1)Brigade Orders 24 August 1776"the Commanding offrs of Battns may send their Knapsacks on board of Ships again if they find any ill Conveniency of them." (2) (1)It seems that many Crown soldiers used only slung blankets during the 1776 campaign, perhaps due to the “ill Conveniency” of their knapsacks, whatever that may mean. Here are two more 1776 references to carrying only blankets and blankets on slings:Orders, 4th Battalion Grenadiers (42nd and 71st Regiments), off Staten Island, 2 August 1776: "When the Men disembark they are to take nothing with them, but 3Shirts 2 prs of hose & their Leggings which are to be put up neatly in their packs, leaving their knapsacks & all their other necessaries on board ship which are carefully to be laid up by the Commanding Officers of Companys in the safest manner they can contrive."Capt. William Leslie, 17th Regiment of Foot, 2 September 1776, “"Bedford Long Island Sept.2nd 1776…

The Day after their Retreat we had orders to march to the ground we are now encamped upon, near the Village of Bedford: It is now a fortnight we have lain upon the ground wrapt in our Blankets, and thank God who supports us when we stand most in need, I have never enjoyed better health in my Life. My whole stock consists of two shirts 2 pr of shoes, 2 Handkerchiefs half of which I use, the other half I carry in my Blanket, like a Pedlar's Pack."61

Preparing for the 1777 campaign the British Guards were slated for another knapsack issue:Secretary at War William Barrington, 2nd Viscount Barrington to Loudoun 7 Sept 1776 His Majesty Orders that for the 1777 Campaign the Detachment is to receive the following CampNecessaries …1062 Haversacks1062 Knapsacks10 Powder Bags(WO4/98 p. 144)Note: Correspondence on pages 150, 157, 171 indicates that only 150 knapsacks per regiment in America were supplied for the 1777 campaign. [That would make 450 total for three battalions.] And in March 1777 the following order was issued:[Guards] Brigade Orders 11 March 1777"The Waistbelts to Carry the Bayonet & to be wore across the Shoulder. The Captains are desired to provide Webbing for Carrying the Mens Blankets according to a pattern to be Seen at the Cantonment of Lt. Colo. Sr. J. Wrottesleys Company. The Serjeants to Observe how they are Sewed."(1) From an original manuscript entitled "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" which is actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day theBrigade for American Service was formed. Manuscript Dept., William L. Clements Library, Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor. (Microfilm available for loan.)

So, were British knapsacks in use up to and including the year 1777 both single-pouch and incapable of accommodating a blanket? Were blanket slings used to carry blankets with knapsacks as well as without? Or were the knapsacks used by Crown forces at the time merely considered cumbersome, and blanket slings thought to be more proper for campaigning soldiers. Added to those questions, we are not at all certain how British soldiers carried their blankets even after double-pouch knapsacks came into use.

To Be Continued...

British Knapsack Timeline, 1758-17941758-1765 (and earlier), Single-pouch purse-like leather knapsack carried by British troops, as pictured in paintings by David Morier (1705-1770) and Edward Penny, R.A. (1714-1791). These knapsacks could not accommodate a blanket.1768, Cuthbertson recommends “square” knapsacks with two shoulder straps.1771, Painting of a private soldier of the 25th Regiment of Foot shows him wearing a hair pack with two shoulder straps. His knapsack seems to be a single-pouch model made of hide covered with hair, and, given the maud slung over his shoulder, could not accommodate a blanket.1774, Timothy Pickering describes a single-pouch, double-shoulder-strap leather knapsack being used in the British Army.1776, An American contractor touts his double-pouch, single-shoulder-strap linen “new InventedNapsack and haversack” to Maryland officials. One pouch was meant for food, the other for soldiers’ necessaries. Some Maryland units are known to have been issued the knapsack, and there is some indication it was used by Pennsylvania troops as well.1776-1777, British regiments are issued knapsacks, but many Crown units use blanket slings instead of packs in these two campaigns. (Possibly because the knapsacks then being used could not accommodate a blanket, which were deemed necessary for American service.)1778, The first known image of a double-pouch British knapsack appears in a 71st Regiment order book. One pouch is shown as holding food, the other, soldiers’ necessaries.1778, On 28 July “1096 Knap & Haversacks” (from the context likely the same as the “new Invented Napsack and haversack”) are sent from Reading, Pennsylvania to supply Continental troops.1780, Benjamin Warner was likely issued his double-pouch double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack while serving with a Continental artillery regiment. `1782, First known documentary references to double-pouch knapsacks.1782, L’Enfant painting of West Point showing soldiers with rolled blankets attached to the top of their knapsacks.1794, The earliest known surviving British double-pouch, double-shoulder-strap linen knapsack, made for the 97th Inverness Regiment, raised in 1794 and disbanded the same year.

Footnotes:

- H. Butterfield, ed., Letters of Benjamin Rush, vol. I (Princeton, N.J., 1951), 154-155.

- 84th Regiment order book, Malcolm Fraser Papers, MG 23, K1,Vol 21, Library and Archives Canada.

- "Orderly Book: British Regiment Footguards, New York and New Jersey," a 1st Battalion

Order Book covering August 1776 to January 1777, Early American Orderly Books, 1748-1817, Collections of the New-York Historical Society (Microfilm Edition - Woodbridge, N.J.: Research Publications, Inc.: 1977), reel 3, document 37.

- Sheldon S. Cohen, "Captain William Leslie's 'Paths of Glory,’" New Jersey History, 108 (1990), 63.

- "Howe Orderly Book 1776-1778" (actually a Brigade of Guards Orderly Book from 1st

Battalion beginning 12 March 1776, the day the Brigade for American Service was formed), Manuscript Department, William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.(Courtesy of Linnea Bass.)

- British Orderly Book [40th Regiment of Foot] April 20, 1777 to August 28, 1777, George Washington Papers, Presidential Papers Microfilm (Washington: Library of Congress, 1961), series 6 (Military Papers, 1755-1798), vol. 1, reel 117. See also, John U. Rees, ed., "`Necessarys

… to be Properley Packd: & Slung in their Blanketts’: Selected Transcriptions 40th Regiment ofFoot Order Book,” http://revwar75.com/library/rees/40th.htm

- "Captured British Orderly Book [49th Regiment], 25 June 1777 to 10 September 1777, . George Washington Papers (microfilm), series 6, vol. 1, reel 117.

- "Orderly Book: First Battalion of Guards, British Army, New York" (covers all but a few days of 1779), Early American Orderly Books, N-YHS (microfilm), reel 6, document 77.

- R. Newsome, ed., "A British Orderly Book, 1780-1781", North Carolina Historical Review, vol. IX (January-October 1932), no. 2, 178-179; no. 3, 286, 287.

- Order book, 43rd Regiment of Foot (British), 23 May 1781 to 25 August 1781, British Museum, London, Mss. 42,449 (transcription by Gilbert V. Riddle).

JOHN REESJohn has been involved in American War for Independence living history for 33 years, and began writing on various aspects of the armies in that conflict in 1986. In addition to publishing articles in journals such as Military Collector & Historian and Brigade Dispatch, he was a regular columnist for the quarterly newsletter Food History News for 15 years writing on soldiers' food, wrote four entries for the Oxford Encyclopedia of American Food and Drink, and thirteen entries for the revised Thomson Gale edition of Boatner’s Encyclopedia of the American Revolution.

Many of his works may be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/jureesarticles .

The Speaker’s House, Trappe PA

This elegant townhome, which reminds you far more of the elegant 18th century townhomes of Philadelphia rather than a home in the rural countryside 25 miles west of that city, was nearly lost to history thanks to modern development. If it had not been for the tireless efforts of concerned citizens, a CVS would stand on this sight today. When you drive up Ridge Pike, following the path that the Continental Army took multiple times into and away from Philly, you see this huge stone house facing down the small shopping center across the street. The years show on this building. The remains of stucco partially obscure the stonework below the roofline, the ghostly outline of an addition to the house that once connected on the eastern wall is all that remains of the general store erected by Frederick Muhlenberg, Lutheran Minister, First Speaker of the House of Representatives, and one of the early judges in Montgomery County PA, son of the famous Henry Muhlenberg: Patriarch of the Lutheran Church in America, and brother to Peter Muhlenberg: the famous Fighting Parson of Virginia during the American Revolution.

Yet, even with the scaffolding wrapped around the house, you can’t help but be amazed by its simple beauty. 4 corner fireplaces in the main section of the house, 2 on each floor. A brand new roof, replacing the Victorian-era modification, restores the houses 18th century roofline; complete with cedar shingles and crown molding copied from the surviving originals found on the property. Behind the main section of the house are the two additions, the latest dates to the early 19th century, within has been found the outline of the original kitchen hearth and bread oven. This is the next restoration project planned. Directly behind the last addition stands the house’s recreated Pennsylvania German Kitchen Garden. Within the white fence, the style of which was copied from local period examples, are 4 central raised beds and others running around the perimeter.

Here, volunteers grow, maintain, and then sell heirloom vegetables, herbs, spices, and flowers that would have been familiar to the people who once called this house home. All of the work, from the masons and carpenters capering on the roof, to the more agriculturally minded watering and pruning plants, everyone working at The Speaker’s House is passionate about bringing the stories that took place in this house and around it alive.

Here, volunteers grow, maintain, and then sell heirloom vegetables, herbs, spices, and flowers that would have been familiar to the people who once called this house home. All of the work, from the masons and carpenters capering on the roof, to the more agriculturally minded watering and pruning plants, everyone working at The Speaker’s House is passionate about bringing the stories that took place in this house and around it alive.

Originally built in 1763 for John Schrack, son of Trappe’s founder, John was the keeper of the original Trappe Tavern, for which the area gets its name. That original tavern stood directly across the street from the house, roughly where a bank is now. After John’s death in 1772 it changed hands multiple times. During the revolution, one of the owners, Johannes Reed, was required to billet soldiers coming from Fort Ticonderoga in New York in his house. Reverend Henry Muhlenberg, who lives just up the road, noted this in his journal. In 1781, Frederick Muhlenberg bought the house and the 50 acres it sat on. This is when he added the 30 ft x 20 ft store, and a further addition on the west side of the house. In 1791, Frederick sold the house sister and his brother in-law Mary and Francis Swaine, who sold the house in 1803 to Charles Albrecht, a musical instrument maker from Philadelphia. Both Frederick and Peter owned Charles Albrecht made pianos in their homes. The house continued to change hands off and on, becoming property of Ursinus College from 1924-1944 and then returning to private ownership again.

Originally built in 1763 for John Schrack, son of Trappe’s founder, John was the keeper of the original Trappe Tavern, for which the area gets its name. That original tavern stood directly across the street from the house, roughly where a bank is now. After John’s death in 1772 it changed hands multiple times. During the revolution, one of the owners, Johannes Reed, was required to billet soldiers coming from Fort Ticonderoga in New York in his house. Reverend Henry Muhlenberg, who lives just up the road, noted this in his journal. In 1781, Frederick Muhlenberg bought the house and the 50 acres it sat on. This is when he added the 30 ft x 20 ft store, and a further addition on the west side of the house. In 1791, Frederick sold the house sister and his brother in-law Mary and Francis Swaine, who sold the house in 1803 to Charles Albrecht, a musical instrument maker from Philadelphia. Both Frederick and Peter owned Charles Albrecht made pianos in their homes. The house continued to change hands off and on, becoming property of Ursinus College from 1924-1944 and then returning to private ownership again.

By the 1990s the house was converted for apartment living and in desperate need of renovation. In 1999 CVS thought about buying the property and demolishing this house. Thankfully, this was not to be, and by 2004 the house was purchased by the non-profit that manages it today.

Though there’s still a lot of work left to be done to bring this house back into its former glory, the group of people who take care of it are more than up to the task. Along with the house itself, it is hoped that the Smoke House, Privy, General Store, and Barn can all be rebuilt in the future on the foundations that remain from the original structures. Whenever you make it out to The Speaker’s House, plan on stopping by again in the future. There’ll be something new to see every time!

KYLE TIMMONSKyle is a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he’s pretty alright. The Speaker's House is in Trappe Pennsylvania and they are hosting a living history event on September 30th, 2017. It has been under renovation since 2004. Come out and support our local history!If you would like to write a short history of your local public historical home please send emails to hm17thblog@gmail.com

KYLE TIMMONSKyle is a long time reenactor, a Combat Medic in the PA National Guard, and currently an employee of the National Park Service. His wife and cat think he’s pretty alright. The Speaker's House is in Trappe Pennsylvania and they are hosting a living history event on September 30th, 2017. It has been under renovation since 2004. Come out and support our local history!If you would like to write a short history of your local public historical home please send emails to hm17thblog@gmail.com

Half a Year in Review

Hello friends and family of the 17th Regiment of Infantry! Hope you are having a great start to the beginning of the month. As the editor, I wanted to take this opportunity to have a website "meeting" with everyone who reads our blog and participates. I wanted to take thank all of my friends who continue to surprise me with their knowledge of the 18th century civilian and military who have all volunteered to write posts so far:

Katherine Becnel Kyle TimmonsJenna SchintzerMark Odintz PhD.Will Tatum PhD.Don HagistCarrie FellowsDamian NiecsiorTim MacdonaldAndrew KirkWilliam MichelAnna Gruber-KieferBrandyn CharltonThank You so much for participating in the blog since we started, it wouldn't be possible without. (I don't think I missed listing anyone but if I did I meant to list you!) Here is a lengthy list of the post highlights that we've had in the last few months:

Kyle TimmonsJenna SchintzerMark Odintz PhD.Will Tatum PhD.Don HagistCarrie FellowsDamian NiecsiorTim MacdonaldAndrew KirkWilliam MichelAnna Gruber-KieferBrandyn CharltonThank You so much for participating in the blog since we started, it wouldn't be possible without. (I don't think I missed listing anyone but if I did I meant to list you!) Here is a lengthy list of the post highlights that we've had in the last few months:

Funcomfortable - Kat BecnelDescribing reenacting in the bitter cold of From Princeton to Trenton in January 2017Feminism and Following - Kat BecnelA farewell opinion piece describing the difference between gal trooping and following the army from a woman's perspective.Opening a Window to the Past - Jenna SchnitzerA conversational discussion piece on the representation of women impressions.Founding the Recreated 17th - Will Tatum PhD.A two part origin story of how the recreated 17th came to be in America.The Physicality of History - Kyle TimmonsA first person simulated account of what 18th Century Soldiers might have had to deal with.Music Made Easy: A Guide to Period Playing - Tim Macdonald A brief guide on the do's and don'ts to period musick playing. An introduction to material culture, in the mix of military discussion.The Things We Carry - Damian NiesciorA short guide to everything an 18th Century Soldier might be seen carrying on his person.The Things We Carry: On the Strength of the Army - Carry FellowsA short guide to everything an 18th Century Follower might be seen carrying on her person.The Making of a "Massacre" Simcoe's Surprise Attack At Hancock's Bridge -William MichelA brief synopsis of the history of The Hancock House in South Jersey opening the discussion to local history and the importance of saving historic homes from the 18thc.On Portraying a Member of the Religious Society of Friends During the American Revolution - Brandyn CharltonA brief discussion of the representation of religion in reenacting with the focus on the religious society of friends developing an introduction to the discussion of religion during the Revolutionary War on the 17th blog.

Changing topic... As editor it's important to listen to opinions and ideas of what people might want to see. If you can tell I've been trying to get a well rounded group of information with everything from; material culture, military history, opinion, and personal reenacting experiences. I've made it my "job" to figure out what the best balance is to share. Not everyone is an active reenactor who seems to read the blog. So what I would like is for active readers to continuously give opinions on what is being posted, so we know what direction to take the discussion.

If you have any requests or topics you would like us to try and discuss please feel free to email me! If you have a topic that you personally would like to discuss please see the Writers Wanted page for more information if you have any questions or comments please use the email listed on that page.

One of my backburner projects for this website has been the 17th Newsletter you see if you open the website for the first time on your browser. Personally it's a process of learning and developing a new skill. As a senior in college you can imagine the lack of time and the ability to spend a good amount of time to learn new programs by myself. Secondly, a long time work in progress has been updating the 17th Gallery. As a film major I am constantly being reminded of the importance of images in making an impression on an audience. With so many great photographers who come to events and share their work with us it is only fair that I have one place to appreciate each of the photographers per event and where their work can be viewed in one place on our website. This project being delayed is another issue of not having enough time. It is just me working on the website so I appreciate everyone's patience.

One of my backburner projects for this website has been the 17th Newsletter you see if you open the website for the first time on your browser. Personally it's a process of learning and developing a new skill. As a senior in college you can imagine the lack of time and the ability to spend a good amount of time to learn new programs by myself. Secondly, a long time work in progress has been updating the 17th Gallery. As a film major I am constantly being reminded of the importance of images in making an impression on an audience. With so many great photographers who come to events and share their work with us it is only fair that I have one place to appreciate each of the photographers per event and where their work can be viewed in one place on our website. This project being delayed is another issue of not having enough time. It is just me working on the website so I appreciate everyone's patience.

That's all for this post! Thanks for participating in the discussion of history, see you at the next event.

Remaining 17th Events 2017

Sept 15 – 17Brandywine, PA / Sandy HollowSept 30Living History at the Speaker's House, Trappe, PAOct 14 - 15Occupied Philadelphia with The Museum of the American RevolutionDec 1 - 3Garrison event at the Old Barracks Museum Trenton, NJ

MARY SHERLOCKMary is a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head' follower for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009.

MARY SHERLOCKMary is a full time Film and Media Arts Student at Temple University, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and the 'head' follower for the 17th Regiment of Infantry. She has been reenacting the Revolutionary War for seven years and is continuing to do so. Mary has been the moderator of the 17th website since 2015 and has been teaching herself html code and css since 2009.

On Portraying a Member of the Religious Society of Friends During the American Revolution

My personal re-enacting story is not unlike many, I have always loved history! From an early age, in fact as far back as I can recall my family were taking vacations that always included an historic site in our plans. My mother tells the story that we would visit these places and I would have so many questions but when she didn’t have an answer I would get upset. She soon resorted to purchasing a guide book at every site we would visit. My first taste of the 18th century was Colonial Williamsburg, as time passed my obsession with history was fueled by my family who would buy me books for every occasion, mostly Civil War at this time. The 18th century interest came after seeing the film Last of the Mohicans (I know but we all had to start somewhere) and instantly knew I had to get into the re-enacting somehow… but that would have to wait.

After my Bachelor’s Degree then Graduate School I finally was at a point that I could think about a hobby. The next several years I participated as much as I could attending events with the Maryland Forces, the 3rd Battalion Pennsylvania Provincial Regiment or Augusta Regiment, then Muskets of the Crown, which was my gateway into the Revolutionary War. Then came the ultimate opportunity, at least for me at that time, I met the Augusta Co. Militia, my re-enacting family and friends for life. I fell in with the ACM after being invited to attend an immersion event at Fort Frederick MD. I finally felt like I “fit”! This group of likeminded people with a laser like focus on accuracy, research and authenticity were just the group I was looking for. I have mostly moved my impression(s) away from the military life and more towards the civilian side of things, however I occasionally field with the ACM for militia company or rifle company events but for the most part my uniforms are retired, replaced by civilian clothing.

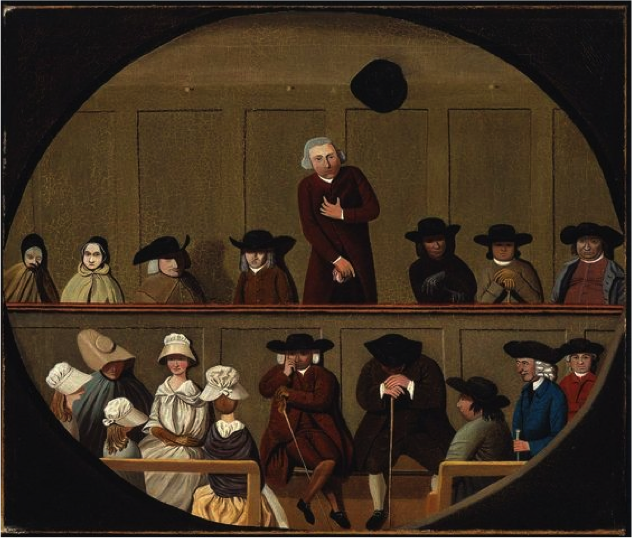

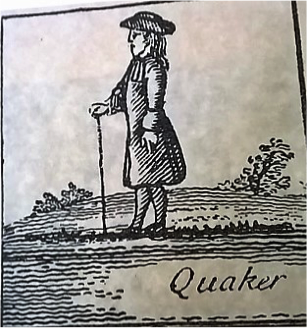

[gallery ids="3126,3127" columns="2" size="medium"]

So, with that said when, where, and why the Quaker impression? It goes back to an event at Monmouth Battlefield where I knew I could not march nor did I have military gear correct for the impression, so civilian it was and lucky for me there was a need for civilians. There were several impressions available and I chose a New Jersey slave owner so my good friend Anna Gruber-Keifer would have someone to play off her Quaker impression with. It was a good thinking moment and I began to research the Quakers (opens HUGE can of worms) …

The next event was the “With Peal to Princeton” march and again the civilian contingent came out but accompanied with that was the AMAZING opportunity to be involved with a promotional shoot for the Museum of the American Revolution. I was asked if I could portray a Quaker, I said yes and knew to do it right I would have to do my homework. I as many had the vision of the Quaker Oats Man in my head as the essential costume of a colonial Quaker. Well I needed to start digging for a better basis than that.

One of the few images available for Quakers of the time is found in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, by an Unidentified Artist. It depicts a Quaker Meeting with what appears one individual standing to give a Testimony. Here was my start, the “plain” attire consistent with the Testimony of Simplicity showed that my brown coat and black waistcoat could work. I would need to construct some breeches for the shoot. Additional research on Quaker dress of the period soon enlightened me further. Although plain dress alone does not make one a Quaker, it was simply an outward expression of faith and adherence to the tenants of the faith.

So profound was the dress that several 18th century authors made mention of it. One example comes from John Wesley (1703-1791) in The Sermons of John Wesley, Sermon 88, On Dress when he encourages his congregation to dress like the Quakers:

So profound was the dress that several 18th century authors made mention of it. One example comes from John Wesley (1703-1791) in The Sermons of John Wesley, Sermon 88, On Dress when he encourages his congregation to dress like the Quakers:

"I conjure you all who have any regard for me, show me before I go hence, that I have not laboured, even in this respect, in vain, for near half a century. Let me see, before I die, a Methodist congregation, full as plain dressed as a Quaker congregation. Only be more consistent with yourselves. Let your dress be cheap as well as plain; otherwise you do but trifle with God, and me, and your own souls. I pray, let there be no costly silks among you, how grave soever they may be. Let there be no Quaker-linen, -- proverbially so called, for their exquisite fineness; no Brussels lace, no elephantine hats or bonnets, -- those scandals of female modesty. Be all of a piece, dressed from head to foot as persons professing godliness; professing to do everything, small and great, with the single view of pleasing God"

(emphasis mine)

In his text “Letters From An American Farmer”, J. Hector St. John De Crevecoeur (1735-1813) writes:

The manners of the Friends are entirely founded on that simplicity which is their boast, and their most distinguished characteristic; and those manners have acquired the authority of laws. Here they are strongly attached to plainness of dress, as well as to that of language;

Additionally I found this description of Quakers from Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) In his book “A Portraiture of Quakerism, Volume 2 published in 1806.

"Peculiar Customs" begins with dress.

"The dress of the Quakers is the first custom of this nature, that I purpose to notice. They stand distinguished by means of it from all other religious bodies. . . . Both sexes are also particular in the choice of the colour of their clothes. All gay colours such as red, blue, green, and yellow, are exploded. Dressing in this manner, a Quaker is known by his apparel through the whole kingdom. This is not the case with any other individuals of the island, except the clergy . . ."

The Quaker impression went over well at Princeton, and the photos were used in a promotional campaign for the new museum. At Princeton, we had some great crowd interaction on the streets and even had the headmistress of the Friends School adjacent to the battlefield come up and engage me and others in some very meaningful conversation. With fuel for the fire I began reading more and researching the Quaker belief system, its origins, its impact on the Revolution etc.

To talk about all aspects of the Quaker religion, its impact on the social and political environment of the American Revolution is well beyond the scope of this post or my limited knowledge. I have, however over the past year begun to dig more deeply, not only on the Quaker faith but its history and impact on history. Some notable Quakers from this period were Thomas Paine author of Common Sense and American General Nathanael Greene. There are examples of Quakers participating on both sides of the conflict. As well as Quaker persecution by both sides. The most common reference to this I have found so far was regarding the “taking of oaths” which is against Quaker teachings. This led many in the faith to be branded as Loyalists and vice versa. I believe this is a good example of the difficulties many Quakers may have faced in keeping strong in faith while living in a “world turned upside down”. Recollections of the war were recorded by the likes of Phebe Mendenhall Thomas, Joseph Townsend, and Daniel Byrnes all of whom were present at the battle of Brandywine. Their stories shed some light into the thoughts and feelings of Quakers before during and after the battle.

I have always been fascinated by religion from an historical perspective so digging into the Quaker belief system was only natural for me. Although not a practicing Quaker in any stretch of the imagination, the idea of attending meeting now and again if for nothing else but to sit quietly and reflect seems a very inviting opportunity. I'll report back if there is interest in my experience.

There are always common questions from the public that arise when I put on my “Quaker” kit. I get a lot of “who are you?” or “what are you doing here?” this one is especially true when at military specific re-enactments. Through trial and error, I have learned it is a good idea if one is going to represent a religion or its members, you had better know as much as you can about that religion. This is one aspect of portraying a Quaker that is an even bigger challenge for reenacting and public interactions. Here in Pennsylvania I have noticed that more often than not, you will come in contact with someone who is either a Quaker or has been exposed to the Quaker religion via a friends’ school etc. So, knowing what you are talking about IS VERY IMPORTANT.

One of the most common question that came up on a trip to the Museum of the American Revolution opening weekend was; “are you Ben Franklin?” As I don’t think myself looking much like this founding father except my generous size, I would explain “no I am portraying a member of the Religious Society of Friends or a Quaker”. Many times, this would be the end of the conversation, but I try to engage the public whenever possible throwing out the bait as to just how did the revolution impact this social, religious and political group of people and vice versa. The individual stories aside, one of the primary areas of conversation I try to engage the public in is the idea of being true to one's beliefs in a world of political change and upheaval? To me this presents a huge talking point and draws some direct relationships between the world of Revolutionary America and the America we are experiencing today.

I take re-enacting not so much as a hobby to be enjoyed on the weekends but more of a calling. I put time and effort not only into my clothing, and elements of material culture, but into my interpretation to the public. I try NOT to perpetuate falsehoods or keep the stereotypes going. I am always trying to learn, expand my knowledge and engage people in the subject I have such passion about. I know I am no expert, I am no classically trained historian I am an amateur at best but I respect the people, places, and things that constitute our collective narrative and strive to present that to those who are willing to listen.

BRANDYN CHARLTONBrandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 21 years working in the clinical, high school, and collegiate practice settings.

BRANDYN CHARLTONBrandyn is a father of three Cora, Clare and Liam, he and his wife Danielle reside in Northumberland Pennsylvania on the Susquehanna River. He has a Bachelor’s degree from Ohio University and a Master’s degree from Edinboro University of PA. He has been a Certified Athletic Trainer for the past 21 years working in the clinical, high school, and collegiate practice settings.

He currently works in the occupational/industrial setting providing ergonomic services to clients in the Harrisburg area.

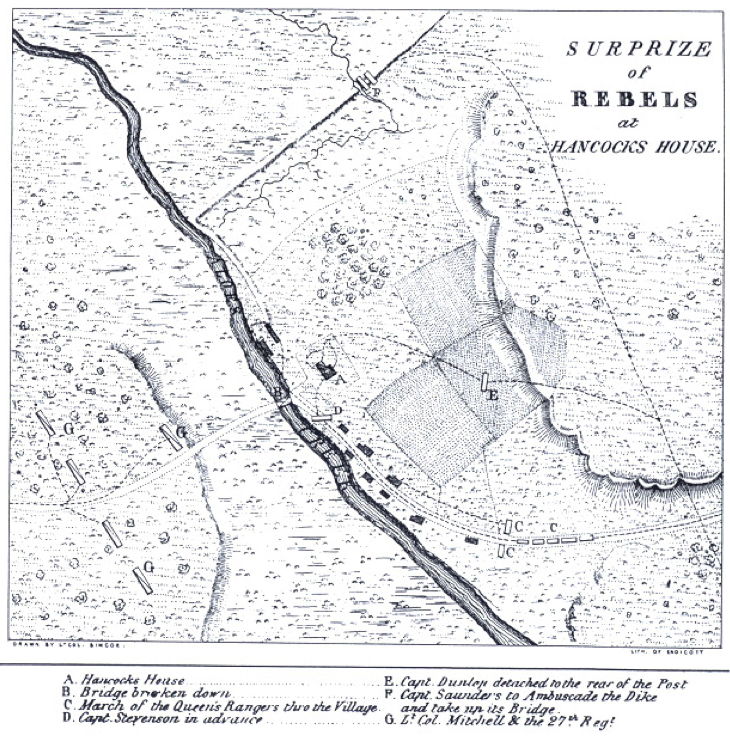

The Making of a “Massacre” Simcoe’s Surprise Attack at Hancock’s Bridge

While the British army was quartered in Philadelphia for the winter of 1777-78 foraging parties were frequently sent out to gather supplies. One such expedition was sent to Salem County, New Jersey in March of 1778. British engineer, Captain John Montressor, recorded in his journal on March 11th:

“The Roebuck removed from the wharves into the stream and the Camilla fell down the river and in the afternoon followed her a detachment of 1,000 men under the command of Col. Mawhood, 17th, 27th, and 46th Regiments, Simcoe’s Rangers.” [1]

Upon arrival to Salem on the 17th of March, Mawhood had all intentions of keeping peace with the local population and to pay for all provisions taken. Major Simcoe writes: “Colonel Mawhood had given the strictest charge against plundering…” [2] but before the expedition was over, the Queen’s Rangers would spark outrage and distain by their treatment of the local rebel militia at Quinton’s Bridge, on the 18th and at Hancock’s Bridge on the 21st. The later would be called a “massacre”.

When the British arrived and took control of the town of Salem, the local militias formed to try and impede Mawhood’s movements. The Alloway, a tidal creek of the Delaware River south of Salem, was chosen as a natural defensive line by the militia to stop the British from moving towards Bridgeton. There were three crossings over the creek: Hancock’s Bridge (closest to the Delaware), Quinton’s Bridge (in the middle) and Thompson’s bridge (furthest east), and each would be guarded.

The first skirmish between Mawhood’s force and the militia occurred on the 18th of March and involved a foraging party of the 17th Regiment of Foot and the Queen’s Rangers. The rebels were bloodied and many were killed or captured, but the defenses held because of timely reinforcements from Bridgeton. Frustrated by the resistance of the locals, Mawhood determined to attack Hancock’s Bridge and gave the task to Major Simcoe and his Rangers, with support from the 27th Regiment of Foot. Simcoe gives his account of the action:

“Colonel Mawhood determined to attack them at [Hancock’s Bridge], where, from all reports, they were assembled to near four hundred men… [The Queen’s Rangers] embarked on the 20th, at night, on board flat bottom boats… everything depended upon surprise. The enemy were nearly double his numbers... [The Rangers] land[ed] in the marshes, at the mouth the Aloes creek… after a march of two miles through marshes… they at length arrived… upon dry land. Here the corps was formed to attack… On approaching the place [Hancock’s Bridge], two sentries were discovered: two men of the light infantry followed them, and as they turned about, bayoneted them…the light infantry… reached Hancock’s house by the road and forced the front door, at the same time that Captain Dunlop… entered the back door; as it was very dark, these companies nearly attacked each other… The surprise was complete, and would have been so, had the whole of the enemy’s force been present, but, fortunately for them, they had quitted it the evening before, leaving a detachment of twenty or thirty men, all of whom were killed… Some very unfortunate circumstances happened here. Among the killed was a friend of the government… old Hancock, the owner of the house… events like these are the real miseries of war.” [3]

Though with somewhat inflated militia numbers, another defense of the Ranger’s actions comes from author James Hannay’s book History of the Queen’s Rangers:

Though with somewhat inflated militia numbers, another defense of the Ranger’s actions comes from author James Hannay’s book History of the Queen’s Rangers:

“Capt. Dunlop's and Stephenson's companies attacked those in the house with such fury that every man in it was killed. This was a lamentable occurrence and has enabled American writers to assert that these men were massacred, but it must be remembered that it was a night attack and that Simcoe's Rangers, instead of this insignificant detachment, expected to meet a force of at least 700 or 800 men, and, of course, a desperate resistance was expected.” [4]

There is still a cloud of confusion surrounding the number of militia actually present that night and how many men, including civilians, were killed. Simcoe states that “all were killed”, but other accounts maintain that there were prisoners taken. British Military Engineer, Archibald Robertson was on the expedition to Salem and recorded in his journal:

“This night [20th of March] Simcoe’s Rangers embarked in the flat boats and went round to the south side of Alloes Creek to surprise the Rebel post at Hancock’s Bridge. The Rangers got behind the Rebels. Killed 16 and took 11 prisoners.” [5]

Lt. Reuel Sayre, one of the militia members attacked at Hancock’s Bridge, recalled later:

“…they came upon us by surprise… All were killed, left for dead or taken prisoners but myself… I had one brother killed and one taken prisoner in this night affair.” [6]

The main purpose of the attack was to gain the south side of the bridge, not to put all to death and quarter was given to some. Simcoe was surprised at the lack of resistance and did not know the Rangers were attacking so few. He expected only the officers to be quartered in the Hancock House, not the entire guard. Captain Carlton Sheppard’s company militia was the only one stationed at the bridge, and was quickly overpowered. When the attack was finished, Simcoe laid the planks down over the bridge in order to confer with Lt. Col. Mitchell of the 27th Regiment, waiting on the other side of the creek, as what to do next:

“Major Simcoe communicated to Colonel Mitchell, that the enemy were at Quinton’s Bridge; that he had good guides to conduct them thither by a private road, that the possession of Hancock’s house secured a retreat. Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell said, that his regiment was much fatigued by the cold, and that he would return to Salem as soon as the troops joined. The ambuscades were of course withdrawn, and the Queen’s Rangers were forming to pass the bridge, when a rebel patrol passed where an ambuscade had been, and discovering the corps, galloped back. Lieutenant-Colonel Mitchell… being informed of the enemy’s patrol, it was thought best to return [to Salem].” [7]

Though the Queen’s Rangers were successful, they again gave up the south side of the Alloway Creek. The outcome of the attack had a demoralizing effect on the militia. When word spread of the affair at Hancock’s Bridge, the resolve to continue a defense at the Alloway dissolved. Colonels Hand and Holme of the militia wrote Governor Livingston:

“We have made our stand on Alloways Creek… but last night the enemy landed out of their boats… and surrounded our guard at Hancock’s Bridge and took and killed almost all of them… we fear they will advance over all these lower counties… we find our numbers at present are not large enough to make a proper stand against them…” [8]

The militia moved south nearly 18 miles to Cumberland County and made the Cohansey River their new defensive line, leaving all of Salem County open to British foraging. After 6 more days of collecting supplies, the British embarked on their ships on the 27th of March and headed back to Philadelphia. The scars left on the inhabitants of Salem County were not easily forgotten. The Hancock House “Massacre” became a rallying cry and may have helped bolster Washington’s ranks in the spring of 1778: