Founding the Recreated 17th: A Research Story, Part 1

This week we have on the blog we have a guest writer who knows the ins and outs of the 17th Regiment of Infantry after establishing the Regiment back in 2002. When the 17th was recreated and established again in 2015 Dr. Will Tatum was the person that the newly formed 17th organization reached out to. Over the next couple weeks there will be a series of articles about the research and the hard work put into creating an organization. Hopefully, our readers will find the writing of Dr. Will Tatum insightful.

Mary Sherlock- An attached Follower of the Recreated 17th Regiment

Founding the Recreated 17th: A Research Story, Part 1

By Will Tatum

Every living history group has a history apart from the subject or topic it represents, an origin story all its own. Most of these stories begin in someone’s basement or garage, in a bar, or result from dissatisfaction with an existing unit. The recreated 17th’s story began with my research at the British National Archives (TNA) over the academic year of 2001-2002. In the summer of 2001 I completed my first year in the hobby and was just beginning to struggle with the process of turning research into a living history interpretation. Other members of the unit to which I belonged at that time suggested that, to avoid hobby politics, it would be best to select a corps around which I could develop my own impression as a sideline project. I reviewed a list of British regiments that had served in America during most or all of the war and had a short list of candidates in mind as I shipped out to Britain that September. Little did I suspect the ah-ha moment that awaited me in the greater London area.

After spending the autumn conducting research in Exeter, where I was studying abroad, I traveled to the TNA for the first time at the end of February 2002. One of my assignments from my then-unit was to track down records relating to soldiers who had served in America, in an attempt to flesh out data from muster rolls. British Army Historian Extraordinaire Don Hagist had suggested examining records from the Royal Hospital Chelsea, which King Charles II established in 1682 to care for deserving army veterans. Only a small set of soldiers were ever selected to receive pensions and even fewer were permitted to reside at the facility, which still exists today. Nevertheless, the surviving records of these “deserving” men provide important insights into the trials and tribulations of the eighteenth-century British soldier. Each of these men had earned referral to the Royal Hospital admission board through exemplary service, which left them physically battered and worn out, no longer capable of fending for themselves.

The specific records in question were contained in WO (War Office) 121, one of several series pertaining to the Royal Hospital’s operations. The documents contained therein mostly date from the mid-1780s onward, with the earlier ones covering men who had served during the American Revolution. While looking through these records, I repeatedly came across discharge documents for soldiers of the 17th Infantry, which I took to be a sign of the regiment that I ought to pursue. If for no other reason, there certainly seemed to be a great deal of surviving documentation on these men. Most of the would-be pensioners I encountered (these documents related to their applications for pensions and did not contain any signification of their success) were simply “worn out in service.” For example, William Dick, a common laborer from Auchtermuckly in Fife, Scotland, played the fife for 17 years before Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Johnson (who took over command of the 17th in 1778) recommended him for a pension in 1787. Joshua Waddington, another 17-year veteran discharged the same year, came from the parish of Litchcliff in Halifax, Yorkshire. At forty-two years of age, with no trade background other than unskilled labor, Waddington was disabled through “having sore legs & being Worn out in the Service.” Private Archibald McDonald of Fort William, Inverness, Scotland, had served 16 years during which he was “twice wounded” and listed as “under Size” at the time of his discharge in 1787.

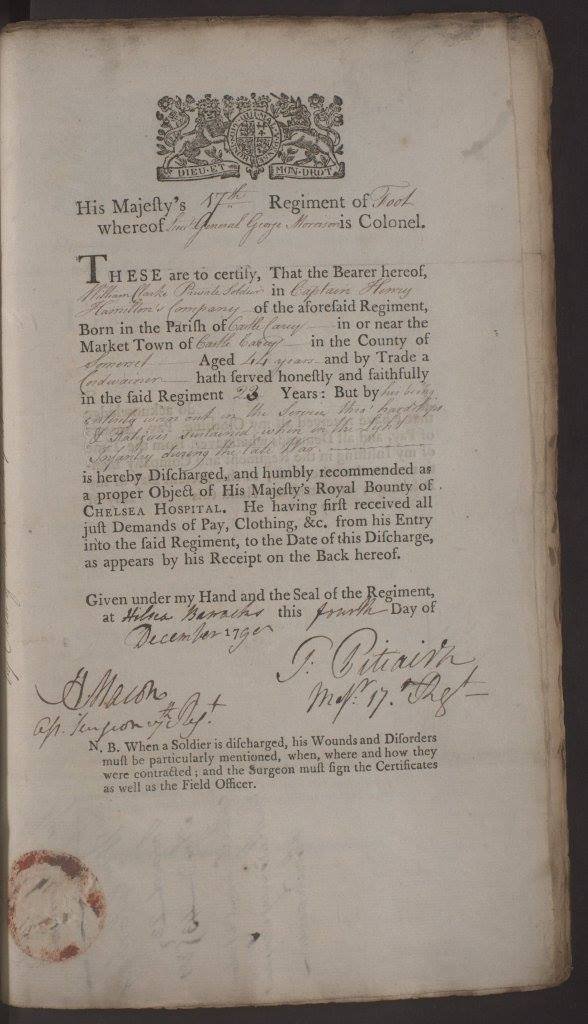

These men, and many others, had served in the regiment during its service in America, though their discharges made no direct comment on that war. Others, however, contained much more pointed statements that testified to the 17th’s extreme service during the Revolution. On December 4, 1790, then-Major T. Pitcairn of the 17th (not a Rev War veteran) signed Private William Clarke’s discharge. On it, Pitcairn noted that 44 year-old Clarke, a 23-year veteran and native of Castle Carey in Somerset, by trade a cordwainer (shoemaker) was “entire worn out in the Service thro’ hardships & Fatigues sustained when in the Lyht [sic] Infantry during the late War.”

Discharge of Private William Clarke, WO121/9/352; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

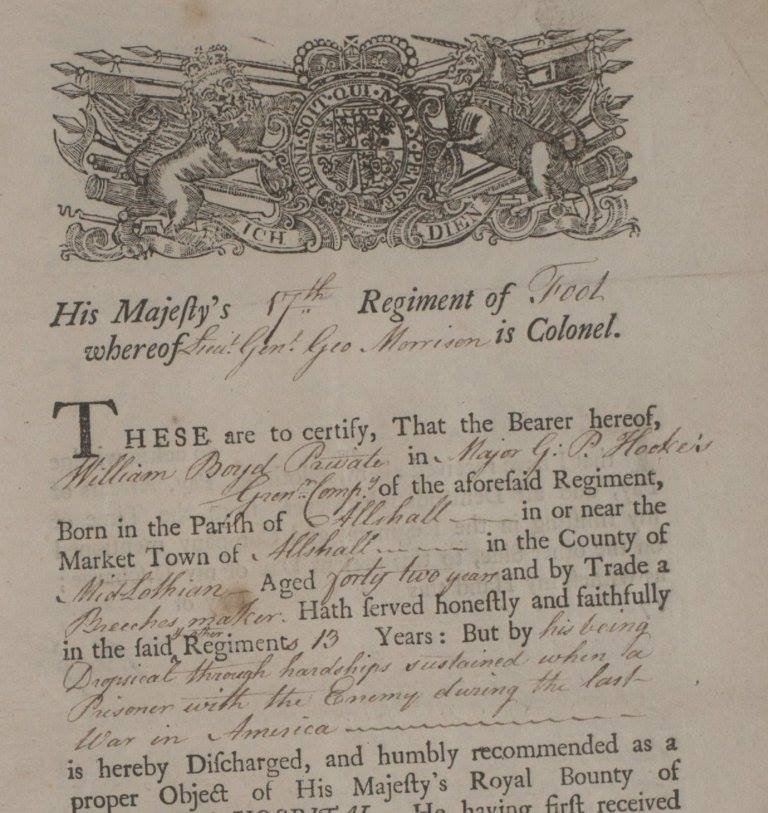

Private John Clarke, a 47 year-old laborer from the town of Hereford in England, a 22 year veteran of the regiment, was discharged the next day, due to “his being Worn out in the Service thro’ hardships sustained during the late War.” Private William Boyd, a 13-year veteran of the regiment and by trade a breeches maker, received his discharge on December 11, 1790, at the age of 42. His paperwork noted that he was “Dropsical through hardships sustained when a Prisoner with the Enemy during the last War in America.” What does “dropsy” mean? Essentially, Private Boyd suffered from uncontrolled water retention between his skin and various body cavities, resulting in painful swellings.

Discharge of Private William Boyd, WO121/9/350; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

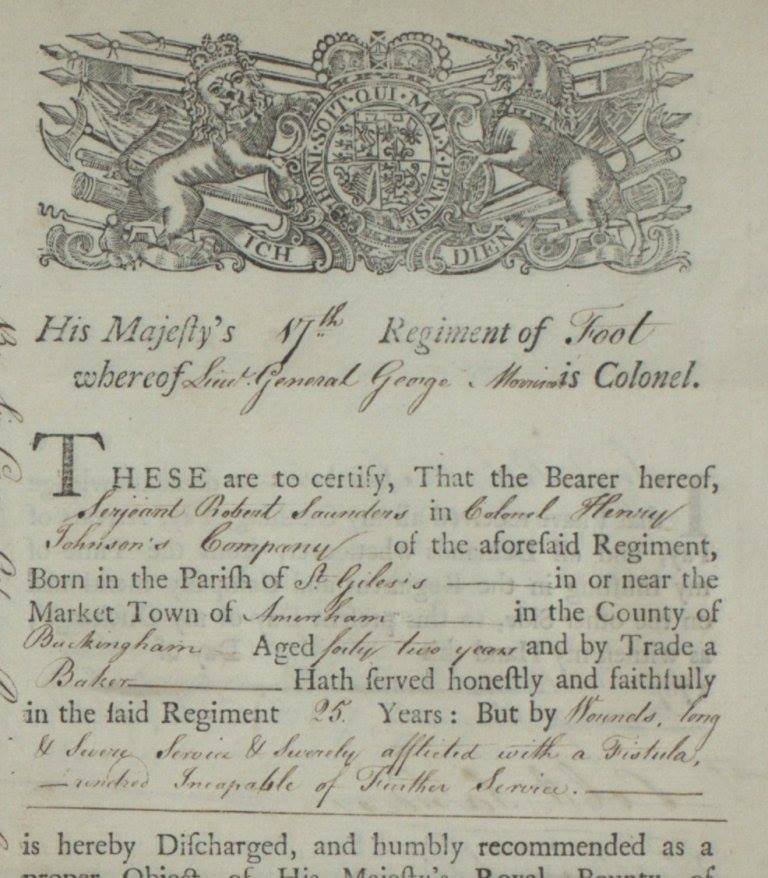

If you think that is bad, I refer you to Serjeant Robert Saunders, a 25-year veteran of the 17th Regiment and a native of Amersham, Buckingham, by trade a baker, discharged on May 10, 1787, at age 42. Saunders had sustained wounds from “long & Severe Service & [was] Severely afflicted with a Fistula, rendred [sic] Incapable of Further Service.” I’ll let you look up what a fistula is on your own. For more tales like these (only with expanded details), check out Don Hagist’s blog British Soldiers, American Revolution.

Discharge of Serjeant Robert Saunder, WO121/2/35; Crown Copyright, Image reproduced by courtesy of The National Archives, London, England

Seeing these documents and considering what they represented on a human scale decided me on exploring the 17th. In subsequent posts, I will explain how the other document series I examined accumulated to form the critical mass for creating a new style of living history group. In this respect, the recreated 17th stood apart from most other units existing at the time and since, in being a response to a research agenda rather than a hobby need. In essence, the horse came before the cart (the history came before the hobby politics) from the beginning.

Will Tatumreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Will Tatumreceived his BA in History from the College of William & Mary in Virginia in 2003, and his MA and PhD from Brown University in Rhode Island in 2004 and 2016. His exploits in Revolutionary War Living History began with a chance encounter at Colonial Williamsburg’s Under the Redcoat event in 2000.

Over the subsequent years, he has traveled throughout the United States and Great Britain researching the eighteenth-century British Army and used the results of those labor to improve living history interpretations. The beginning of this journey in 2001 marked the start of the current recreated 17th Infantry.